A guide to focus group interviews

Last updated

12 March 2023

Reviewed by

Jean Kaluza

Analyze focus group sessions

Dovetail streamlines focus group research to help you understand the responses and find patterns faster

- What is a focus group?

A focus group is a technique in qualitative research to collect data through group discussions. A group of five to 10 people answers questions on a specific topic in a moderated setting.

The person who runs the focus group is the moderator. They’re in charge of leading the members through the discussion and taking notes of the group’s opinions.

- Characteristics of a focus group

The characteristics of a focus group include:

A specific discussion topic

A facilitator

Carefully planned group discussions

Similar characteristics across the participants

- Five different types of focus groups

There are several types of focus groups . They include:

1. Dual moderator focus group

This involves two moderators, each with different roles. For example, one may take notes while the other facilitates the discussion.

2. Two-way focus group

One group watches and listens to what another group is discussing and later comments on what they have heard or observed. Again, both groups have facilitators.

3. Client-involvement focus group

This focus group includes representatives from the company you’re studying. The client is part of the discussion and steers the discussion toward the main objective.

4. Mini focus group

A mini focus group involves a smaller group of participants, typically four or five.

5. Online focus groups

In online focus groups, participants contribute to the discussion remotely via video chat.

- The purpose of focus group interviews

The primary purpose of a focus group interview is to gather qualitative insights from people with specific knowledge of a particular topic or product. Other purposes of focus groups include:

Identifying how people use products

Testing new ideas

Understanding customer needs

Understanding customers' dissatisfaction with certain products

Listening to your customers’ discussion about your products

Viewing brand perception in the community

- When to use a focus group interview

You should use focus group interviews when:

Exploring or generating hypotheses

You want a better understanding of the results of a primary quantitative research

Seeking a more interactive research method

You can’t explain a problem by any other method

Understanding complex phenomena, behaviors, or motivations

- Logistical considerations of a focus group

Some of the logistical considerations to prioritize are:

Recruiting the right participants

Since focus groups rely on a small number of respondents, it’s essential to recruit suitable participants for effective results.

The common criteria for selecting the right participants are choosing members with knowledge of the subject. Other popular recruiting methods are:

Random selection : Drawing names of participants from a large group of people

Nomination : Where key individuals suggest people they think are a good choice

Volunteering : Where you recruit participants through newspaper ads or flyers

Selecting the right moderator

It’s necessary to select the right facilitator to steer the discussion in the right direction.

They should also have:

Adequate topic knowledge

Facilitator experience

Knowledge of focus group techniques and moderation

The ability to empathize with the group

The skills to direct the discussion

Choosing the venue

You should carefully choose the location to match the expectations of the respondent group.

It should be accessible to all, have ample parking, and be well-connected by public transport. This ensures that participants arrive on time without any difficulties.

The room should be free from distractions and the appropriate size for the participants. Participants are more likely to feel comfortable expressing opinions in a relaxing environment.

Ensuring working equipment

The moderator should check the equipment beforehand to ensure it works. This includes ensuring audio or video recording tools are well-serviced and functioning as required.

You need to inform the participants that you may record the session. It’s important to receive permission to record and get participants to sign NDAs if they’re discussing sensitive ideas.

Selecting the right incentives

It’s standard practice to offer respondents incentives to thank them for showing up.

You may need to provide incentives to keep the participants focused and content.

Some incentive ideas include:

Monetary compensation

Company merchandise

Prize draws

Free transport

Proper time management

When conducting focus group interviews, keep the sessions short. Focus group interviews should typically last 60–90 minutes. The longer the discussion, the less interested the participants will likely be, so the sessions become less lively.

- How to conduct focus group interviews

Follow these steps when conducting a focus group interview:

Prepare an interview schedule

First, write out a list of questions and topics for the discussion. This ensures clear objectives from the start. Keep your interview questions:

Short and clear

On topic and in line with your research objectives

Unambiguously worded

Well-structured

With the efficient use of an interview guide, the moderator will periodically check to ensure that the discussion is progressing appropriately.

Moderating involves keeping the interactions flowing and guiding the group whenever they veer off to irrelevant topics.

While moderating, the facilitator should let the participants know they are part of the team. In addition, the moderator should use pauses and probes.

Examples of probes include:

Please elaborate more

Can you tell me more about that?

The moderator can curb distractions with:

We’re not discussing that topic at the moment

That sounds unrelated; maybe we can come back to that later

Additionally, the moderator must regulate and control group dynamics. This includes research-endangering social conformity.

Should your group have a louder or more persuasive voice, the rest could naturally agree with their perspectives and opinions. This can quickly turn a diverse focus group and data set into an expensive single-minded response from your whole group.

Tactics to consider include timing and moderating responses carefully, providing post-its for participants to respond with, or creating exercises to ensure every voice is equal.

Starting the focus group

The moderator should spend the first few minutes of the discussion creating an open and permissive atmosphere for all the participants. The moderator can start by welcoming the members and giving an overview of the discussion.

Leading the discussion

Once the moderator establishes rapport, they set ground rules and welcome follow-up questions.

The moderator should ask questions methodically. Once they’ve asked all the questions, it’s time to wrap up with final thoughts.

Finally, the moderator can thank the participants and end the session.

- Addressing common focus group challenges

Here are three common challenges of focus groups and how to address them.

1. Managing group dynamics

Domineering people can lead a discussion and skew research findings. If more than one strong personality is in the room, hostility or outright fights can derail productivity.

Agreeable or more introverted individuals in the group may go along with whatever voice they are most persuaded or intimidated by. This means you may never discover their true opinions.

Consider the following tips to make all participants comfortable during the discussion:

Start the session with a warm-up activity for all members to get comfortable

Use icebreakers such as two truths and one lie

Use a mix of written and verbal participation techniques for maximum contribution

2. Facilitator bias

Moderators can negatively impact the outcome of the discussion. This happens when the facilitator selects people with positive responses that align with their opinions.

Although bias is challenging to eliminate, noting potential sources of bias can address the challenge. Moderators can mitigate bias by remaining objective, being self-aware, using neutral language, and minding body language.

3. The results may not be representative

Often, you cannot generalize the results from a small group to a larger group. Therefore, you should choose participants who represent the target audience to address this challenge.

- Advantages of focus groups

Focus groups offer several advantages, including:

Understanding the subject matter and customer base in their own words

Recording facial expressions and other nonverbal signs

Generating results in 90-minute sessions

A deeper understanding of the respondents through personal interaction

Listening in on conversations about your product you otherwise would never hear

Disadvantages of focus groups

Face-to-face focus group interviews also have a few drawbacks.

Geographical restrictions can cause issues if participants have to travel to participate.

Some members may shy away and contribute less to the discussion.

The discussion may veer toward irrelevant topics, so a strong facilitator is crucial.

The follow-up probes might take longer.

Paying a group rather than individuals can be costly and risks conforming to one voice.

- Sample focus group interview questions

The interview questions should be engaging, explorative, and open-ended.

For instance, when discussing a topic that tests a phone's performance in the market:

Engagement questions to ask a focus group about their phones:

Which is your favorite phone?

What do you consider when buying a new phone?

Exploration questions can include:

Who influenced you to purchase the phone you are currently using?

What are the advantages of using the phone brand?

How do you feel about changing to other brands?

Exit questions ensure nothing has been left out. Sample interview questions could include:

Is there anyone who would like to add to what we’ve said?

Does anyone have any final thoughts?

How are focus group interviews conducted?

Focus groups involve 6–10 respondents coming together for a guided discussion. During the session, the members answer predetermined questions to gather their opinions and motivations about a particular topic.

Why are focus group interviews better?

Typically, this research method can unearth detailed information while observing the respondent's body language. You can collect multiple findings while witnessing the group's thought process.

What should be discussed in a focus group?

Participants of focus groups are free to share their opinions, insights, and knowledge about a specific topic.

How do you plan a focus group question?

The questions in a focus group discussion should be explorative, open-ended, carefully worded, and unbiased. You should write them to fit what your research study is trying to uncover.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 9 November 2024

Last updated: 11 January 2024

Last updated: 14 February 2024

Last updated: 27 January 2024

Last updated: 17 January 2024

Last updated: 14 November 2023

Last updated: 20 January 2024

Last updated: 19 November 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2024

Last updated: 25 November 2024

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, a whole new way to understand your customer is here, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- Privacy Policy

Home » Focus Groups – Steps, Examples and Guide

Focus Groups – Steps, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

Focus groups are a qualitative research method used to gather in-depth insights from a small group of people on a specific topic, product, or concept. They provide valuable perspectives by facilitating open discussion, allowing researchers to observe participants’ thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in real-time. This guide explores the steps to conducting focus groups, examples, and practical tips for organizing a successful session.

Focus Group

A focus group is a carefully planned discussion involving a small number of participants who share their opinions and attitudes about a specific topic. Guided by a moderator, focus groups encourage interactive discussions that yield qualitative insights, making them especially useful in fields like marketing, social science, product development, and healthcare.

Key Features of Focus Groups :

- Small Group Size : Typically 6–10 participants, which allows for effective discussion without overwhelming participants.

- Guided Discussion : A moderator facilitates the conversation to keep it on topic while allowing for natural flow.

- In-Depth Insights : Focus groups provide detailed insights into participants’ thoughts and emotions, which can be difficult to obtain through surveys or interviews.

Purpose of Focus Groups

The main purpose of a focus group is to explore participants’ attitudes, beliefs, and opinions. Focus groups help to:

- Understand Customer Preferences : Collect feedback on products or services directly from users.

- Refine Ideas and Concepts : Test ideas or concepts by understanding how participants perceive them.

- Explore Social Attitudes : Identify social attitudes, behaviors, and motivations on complex issues.

Steps to Conduct a Focus Group

Step 1: define objectives.

The first step is to clarify what you hope to achieve from the focus group. Define clear research objectives and questions that guide the focus group discussion.

Example Objective : A healthcare organization may aim to understand patients’ experiences with telemedicine services to improve user satisfaction.

Step 2: Recruit Participants

Select participants who represent your target audience. Recruitment can be done through emails, social media, flyers, or professional recruiters. Ensure participants have diverse backgrounds to provide well-rounded insights but also share common characteristics relevant to the study.

Participant Selection Criteria :

- Demographics (age, gender, location)

- Experience level (users of a product, service, or issue)

- Specific interests or behaviors relevant to the research

Step 3: Develop a Discussion Guide

A discussion guide is essential for structuring the session. It includes open-ended questions that encourage participants to share their thoughts and feelings. Questions should be straightforward, unbiased, and designed to stimulate conversation.

Example Questions :

- “What are your initial impressions of this product?”

- “What challenges have you faced with telemedicine appointments?”

- “How would you compare this service to others you’ve used?”

Step 4: Choose a Moderator and Prepare the Setting

The moderator plays a critical role in guiding the conversation and ensuring all voices are heard. An ideal moderator is neutral, skilled in communication, and experienced in group facilitation. The setting should be comfortable, private, and conducive to open discussion.

Moderator Responsibilities :

- Encourage participation from all members.

- Keep the discussion on topic without leading participants.

- Manage group dynamics to avoid dominant voices overshadowing others.

Step 5: Conduct the Focus Group

Begin by welcoming participants and explaining the purpose of the session. Set guidelines for respectful conversation and assure confidentiality. Use the discussion guide to direct the conversation while allowing participants to express themselves freely. Take notes, or record the session (with participants’ consent) for accurate analysis later.

Key Points During the Session :

- Introduce Topics Naturally : Start with broad questions and narrow down to specifics.

- Encourage Interaction : Foster group interaction by prompting participants to respond to each other’s ideas.

- Observe Nonverbal Cues : Pay attention to body language, tone, and facial expressions, which can provide additional insights.

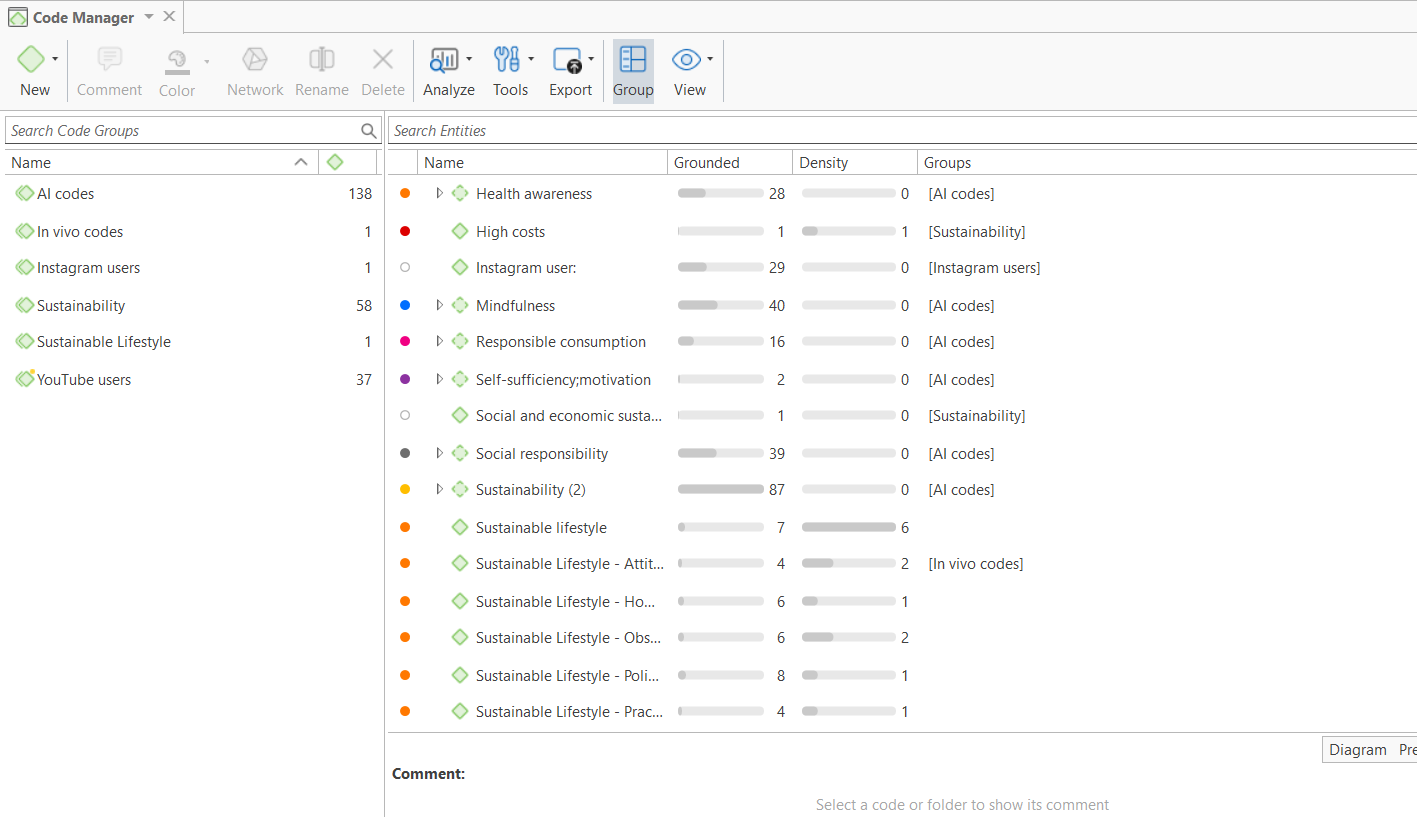

Step 6: Analyze Results

After the session, transcribe the recording and review the notes to identify common themes, patterns, or differences in responses. Coding responses and grouping them by themes can help organize insights for analysis.

Analysis Process :

- Identify recurring themes or patterns.

- Note unique or unexpected insights that may require further exploration.

- Summarize findings based on the research objectives.

Step 7: Report Findings

Present the findings in a clear, structured format, often including a summary, key insights, and recommendations based on the focus group data. Visual aids, like charts or quotes, can help communicate results effectively.

Example of a Focus Group Report Structure :

- Introduction : State the research objectives and purpose of the focus group.

- Methodology : Describe participant demographics, recruitment, and the session process.

- Findings : Summarize key themes, quotes, and observations.

- Conclusion and Recommendations : Provide actionable insights or suggestions based on the findings.

Examples of Focus Group Applications

- Product Development : A tech company conducts a focus group with smartphone users to gather feedback on a new phone model’s design, usability, and features.

- Healthcare : A hospital holds a focus group with patients who use telemedicine to understand their satisfaction levels and identify areas for improvement.

- Education : An educational institution organizes a focus group with students to explore their experiences with online learning platforms and identify potential challenges.

- Public Policy : A government agency conducts focus groups with community members to understand opinions about new public health initiatives, such as vaccination programs.

Tips for Conducting Successful Focus Groups

- Create a Comfortable Atmosphere : Make participants feel comfortable and valued to encourage openness and honesty.

- Keep Questions Neutral : Avoid leading questions that might influence participants’ responses.

- Engage All Participants : Use strategies to involve quieter participants while managing dominant voices.

- Stay Flexible : While the discussion guide provides structure, allow flexibility to follow interesting tangents.

- Respect Time : Keep the session within the planned timeframe, usually lasting 60–90 minutes, to avoid participant fatigue.

Advantages and Limitations of Focus Groups

Advantages :

- Rich Data : Provides deep insights into participants’ thoughts, feelings, and motivations.

- Interactive Discussion : Allows participants to build on each other’s ideas, generating new perspectives.

- Efficient : Enables researchers to gather diverse opinions in a relatively short time.

Limitations :

- Potential for Bias : The moderator’s influence or dominant participants can sway the discussion.

- Limited Generalizability : Findings may not represent the broader population due to small sample size.

- Time and Cost : Organizing and analyzing focus group data can be resource-intensive.

Focus groups are a powerful tool for gathering qualitative insights that provide depth and context to research questions. By following the steps outlined here—defining objectives, recruiting participants, developing a guide, and conducting thorough analysis—researchers can effectively use focus groups to explore complex issues. While focus groups have some limitations, their ability to capture detailed and interactive feedback makes them invaluable for studies in fields like marketing, healthcare, and public policy.

- Morgan, D. L. (1997). Focus Groups as Qualitative Research . Sage Publications.

- Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. A. (2014). Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research . Sage Publications.

- Flick, U. (2018). An Introduction to Qualitative Research . Sage Publications.

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods . Sage Publications.

- Rabiee, F. (2004). Focus-group interview and data analysis . Proceedings of the Nutrition Society , 63(4), 655-660.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Textual Analysis – Types, Examples and Guide

Experimental Design – Types, Methods, Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Triangulation in Research – Types, Methods and...

Basic Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Chapter 12. Focus Groups

Introduction.

Focus groups are a particular and special form of interviewing in which the interview asks focused questions of a group of persons, optimally between five and eight. This group can be close friends, family members, or complete strangers. They can have a lot in common or nothing in common. Unlike one-on-one interviews, which can probe deeply, focus group questions are narrowly tailored (“focused”) to a particular topic and issue and, with notable exceptions, operate at the shallow end of inquiry. For example, market researchers use focus groups to find out why groups of people choose one brand of product over another. Because focus groups are often used for commercial purposes, they sometimes have a bit of a stigma among researchers. This is unfortunate, as the focus group is a helpful addition to the qualitative researcher’s toolkit. Focus groups explicitly use group interaction to assist in the data collection. They are particularly useful as supplements to one-on-one interviews or in data triangulation. They are sometimes used to initiate areas of inquiry for later data collection methods. This chapter describes the main forms of focus groups, lays out some key differences among those forms, and provides guidance on how to manage focus group interviews.

Focus Groups: What Are They and When to Use Them

As interviews, focus groups can be helpfully distinguished from one-on-one interviews. The purpose of conducting a focus group is not to expand the number of people one interviews: the focus group is a different entity entirely. The focus is on the group and its interactions and evaluations rather than on the individuals in that group. If you want to know how individuals understand their lives and their individual experiences, it is best to ask them individually. If you want to find out how a group forms a collective opinion about something (whether a product or an event or an experience), then conducting a focus group is preferable. The power of focus groups resides in their being both focused and oriented to the group . They are best used when you are interested in the shared meanings of a group or how people discuss a topic publicly or when you want to observe the social formation of evaluations. The interaction of the group members is an asset in this method of data collection. If your questions would not benefit from group interaction, this is a good indicator that you should probably use individual interviews (chapter 11). Avoid using focus groups when you are interested in personal information or strive to uncover deeply buried beliefs or personal narratives. In general, you want to avoid using focus groups when the subject matter is polarizing, as people are less likely to be honest in a group setting. There are a few exceptions, such as when you are conducting focus groups with people who are not strangers and/or you are attempting to probe deeply into group beliefs and evaluations. But caution is warranted in these cases. [1]

As with interviewing in general, there are many forms of focus groups. Focus groups are widely used by nonresearchers, so it is important to distinguish these uses from the research focus group. Businesses routinely employ marketing focus groups to test out products or campaigns. Jury consultants employ “mock” jury focus groups, testing out legal case strategies in advance of actual trials. Organizations of various kinds use focus group interviews for program evaluation (e.g., to gauge the effectiveness of a diversity training workshop). The research focus group has many similarities with all these uses but is specifically tailored to a research (rather than applied) interest. The line between application and research use can be blurry, however. To take the case of evaluating the effectiveness of a diversity training workshop, the same interviewer may be conducting focus group interviews both to provide specific actionable feedback for the workshop leaders (this is the application aspect) and to learn more about how people respond to diversity training (an interesting research question with theoretically generalizable results).

When forming a focus group, there are two different strategies for inclusion. Diversity focus groups include people with diverse perspectives and experiences. This helps the researcher identify commonalities across this diversity and/or note interactions across differences. What kind of diversity to capture depends on the research question, but care should be taken to ensure that those participating are not set up for attack from other participants. This is why many warn against diversity focus groups, especially around politically sensitive topics. The other strategy is to build a convergence focus group , which includes people with similar perspectives and experiences. These are particularly helpful for identifying shared patterns and group consensus. The important thing is to closely consider who will be invited to participate and what the composition of the group will be in advance. Some review of sampling techniques (see chapter 5) may be helpful here.

Moderating a focus group can be a challenge (more on this below). For this reason, confining your group to no more than eight participants is recommended. You probably want at least four persons to capture group interaction. Fewer than four participants can also make it more difficult for participants to remain (relatively) anonymous—there is less of a group in which to hide. There are exceptions to these recommendations. You might want to conduct a focus group with a naturally occurring group, as in the case of a family of three, a social club of ten, or a program of fifteen. When the persons know one another, the problems of too few for anonymity don’t apply, and although ten to fifteen can be unwieldy to manage, there are strategies to make this possible. If you really are interested in this group’s dynamic (not just a set of random strangers’ dynamic), then you will want to include all its members or as many as are willing and able to participate.

There are many benefits to conducting focus groups, the first of which is their interactivity. Participants can make comparisons, can elaborate on what has been voiced by another, and can even check one another, leading to real-time reevaluations. This last benefit is one reason they are sometimes employed specifically for consciousness raising or building group cohesion. This form of data collection has an activist application when done carefully and appropriately. It can be fun, especially for the participants. Additionally, what does not come up in a focus group, especially when expected by the researcher, can be very illuminating.

Many of these benefits do incur costs, however. The multiplicity of voices in a good focus group interview can be overwhelming both to moderate and later to transcribe. Because of the focused nature, deep probing is not possible (or desirable). You might only get superficial thinking or what people are willing to put out there publicly. If that is what you are interested in, good. If you want deeper insight, you probably will not get that here. Relatedly, extreme views are often suppressed, and marginal viewpoints are unspoken or, if spoken, derided. You will get the majority group consensus and very little of minority viewpoints. Because people will be engaged with one another, there is the possibility of cut-off sentences, making it even more likely to hear broad brush themes and not detailed specifics. There really is very little opportunity for specific follow-up questions to individuals. Reading over a transcript, you may be frustrated by avenues of inquiry that were foreclosed early.

Some people expect that conducting focus groups is an efficient form of data collection. After all, you get to hear from eight people instead of just one in the same amount of time! But this is a serious misunderstanding. What you hear in a focus group is one single group interview or discussion. It is not the same thing at all as conducting eight single one-hour interviews. Each focus group counts as “one.” Most likely, you will need to conduct several focus groups, and you can design these as comparisons to one another. For example, the American Sociological Association (ASA) Task Force on First-Generation and Working-Class Persons in Sociology began its study of the impact of class in sociology by conducting five separate focus groups with different groups of sociologists: graduate students, faculty (in general), community college faculty, faculty of color, and a racially diverse group of students and faculty. Even though the total number of participants was close to forty, the “number” of cases was five. It is highly recommended that when employing focus groups, you plan on composing more than one and at least three. This allows you to take note of and potentially discount findings from a group with idiosyncratic dynamics, such as where a particularly dominant personality silences all other voices. In other words, putting all your eggs into a single focus group basket is not a good idea.

How to Conduct a Focus Group Interview/Discussion

Advance preparations.

Once you have selected your focus groups and set a date and time, there are a few things you will want to plan out before meeting.

As with interviews, you begin by creating an interview (or discussion) guide. Where a good one-on-one interview guide should include ten to twelve main topics with possible prompts and follow-ups (see the example provided in chapter 11), the focus group guide should be more narrowly tailored to a single focus or topic area. For example, a focus might be “How students coped with online learning during the pandemic,” and a series of possible questions would be drafted that would help prod participants to think about and discuss this topic. These questions or discussion prompts can be creative and may include stimulus materials (watching a video or hearing a story) or posing hypotheticals. For example, Cech ( 2021 ) has a great hypothetical, asking what a fictional character should do: keep his boring job in computers or follow his passion and open a restaurant. You can ask a focus group this question and see what results—how the group comes to define a “good job,” what questions they ask about the hypothetical (How boring is his job really? Does he hate getting up in the morning, or is it more of an everyday tedium? What kind of financial support will he have if he quits? Does he even know how to run a restaurant?), and how they reach a consensus or create clear patterns of disagreement are all interesting findings that can be generated through this technique.

As with the above example (“What should Joe do?”), it is best to keep the questions you ask simple and easily understood by everyone. Thinking about the sequence of the questions/prompts is important, just as it is in conducting any interviews.

Avoid embarrassing questions. Always leave an out for the “I have a friend who X” response rather than pushing people to divulge personal information. Asking “How do you think students coped?” is better than “How did you cope?” Chances are, some participants will begin talking about themselves without you directly asking them to do so, but allowing impersonal responses here is good. The group itself will determine how deep and how personal it wants to go. This is not the time or place to push anyone out of their comfort zone!

Of course, people have different levels of comfort talking publicly about certain topics. You will have provided detailed information to your focus group participants beforehand and secured consent. But even so, the conversation may take a turn that makes someone uncomfortable. Be on the lookout for this, and remind everyone of their ability to opt out—to stay silent or to leave if necessary. Rather than call attention to anyone in this way, you also want to let everyone know they are free to walk around—to get up and get coffee (more on this below) or use the restroom or just step out of the room to take a call. Of course, you don’t really want anyone to do any of these things, and chances are everyone will stay seated during the hour, but you should leave this “out” for those who need it.

Have copies of consent forms and any supplemental questionnaire (e.g., demographic information) you are using prepared in advance. Ask a friend or colleague to assist you on the day of the focus group. They can be responsible for making sure the recording equipment is functioning and may even take some notes on body language while you are moderating the discussion. Order food (coffee or snacks) for the group. This is important! Having refreshments will be appreciated by your participants and really damps down the anxiety level. Bring name tags and pens. Find a quiet welcoming space to convene. Often this is a classroom where you move chairs into a circle, but public libraries often have meeting rooms that are ideal places for community members to meet. Be sure that the space allows for food.

Researcher Note

When I was designing my research plan for studying activist groups, I consulted one of the best qualitative researchers I knew, my late friend Raphael Ezekiel, author of The Racist Mind . He looked at my plan to hand people demographic surveys at the end of the meetings I planned to observe and said, “This methodology is missing one crucial thing.” “What?” I asked breathlessly, anticipating some technical insider tip. “Chocolate!” he answered. “They’ll be tired, ready to leave when you ask them to fill something out. Offer an incentive, and they will stick around.” It worked! As the meetings began to wind down, I would whip some bags of chocolate candies out of my bag. Everyone would stare, and I’d say they were my thank-you gift to anyone who filled out my survey. Once I learned to include some sugar-free candies for diabetics, my typical response rate was 100 percent. (And it gave me an additional class-culture data point by noticing who chose which brand; sure enough, Lindt balls went faster at majority professional-middle-class groups, and Hershey’s minibars went faster at majority working-class groups.)

—Betsy Leondar-Wright, author of Missing Class , coauthor of The Color of Wealth , associate professor of sociology at Lasell University, and coordinator of staffing at the Mission Project for Class Action

During the Focus Group

As people arrive, greet them warmly, and make sure you get a signed consent form (if not in advance). If you are using name tags, ask them to fill one out and wear it. Let them get food and find a seat and do a little chatting, as they might wish. Once seated, many focus group moderators begin with a relevant icebreaker. This could be simple introductions that have some meaning or connection to the focus. In the case of the ASA task force focus groups discussed above, we asked people to introduce themselves and where they were working/studying (“Hi, I’m Allison, and I am a professor at Oregon State University”). You will also want to introduce yourself and the study in simple terms. They’ve already read the consent form, but you would be surprised at how many people ignore the details there or don’t remember them. Briefly talking about the study and then letting people ask any follow-up questions lays a good foundation for a successful discussion, as it reminds everyone what the point of the event is.

Focus groups should convene for between forty-five and ninety minutes. Of course, you must tell the participants the time you have chosen in advance, and you must promptly end at the time allotted. Do not make anyone nervous by extending the time. Let them know at the outset that you will adhere to this timeline. This should reduce the nervous checking of phones and watches and wall clocks as the end time draws near.

Set ground rules and expectations for the group discussion. My preference is to begin with a general question and let whoever wants to answer it do so, but other moderators expect each person to answer most questions. Explain how much cross-talk you will permit (or encourage). Again, my preference is to allow the group to pick up the ball and run with it, so I will sometimes keep my head purposefully down so that they engage with one another rather than me, but I have seen other moderators take a much more engaged position. Just be clear at the outset about what your expectations are. You may or may not want to explain how the group should deal with those who would dominate the conversation. Sometimes, simply stating at the outset that all voices should be heard is enough to create a more egalitarian discourse. Other times, you will have to actively step in to manage (moderate) the exchange to allow more voices to be heard. Finally, let people know they are free to get up to get more coffee or leave the room as they need (if you are OK with this). You may ask people to refrain from using their phones during the duration of the discussion. That is up to you too.

Either before or after the introductions (your call), begin recording the discussion with their collective permission and knowledge . If you have brought a friend or colleague to assist you (as you should), have them attend to the recording. Explain the role of your colleague to the group (e.g., they will monitor the recording and will take short notes throughout to help you when you read the transcript later; they will be a silent observer).

Once the focus group gets going, it may be difficult to keep up. You will need to make a lot of quick decisions during the discussion about whether to intervene or let it go unguided. Only you really care about the research question or topic, so only you will really know when the discussion is truly off topic. However you handle this, keep your “participation” to a minimum. According to Lune and Berg ( 2018:95 ), the moderator’s voice should show up in the transcript no more than 10 percent of the time. By the way, you should also ask your research assistant to take special note of the “intensity” of the conversation, as this may be lost in a transcript. If there are people looking overly excited or tapping their feet with impatience or nodding their heads in unison, you want some record of this for future analysis.

I’m not sure why this stuck with me, but I thought it would be interesting to share. When I was reviewing my plan for conducting focus groups with one of my committee members, he suggested that I give the participants their gift cards first. The incentive for participating in the study was a gift card of their choice, and typical processes dictate that participants must complete the study in order to receive their gift card. However, my committee member (who is Native himself) suggested I give it at the beginning. As a qualitative researcher, you build trust with the people you engage with. You are asking them to share their stories with you, their intimate moments, their vulnerabilities, their time. Not to mention that Native people are familiar with being academia’s subjects of interest with little to no benefit to be returned to them. To show my appreciation, one of the things I could do was to give their gifts at the beginning, regardless of whether or not they completed participating.

—Susanna Y. Park, PhD, mixed-methods researcher in public health and author of “How Native Women Seek Support as Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence: A Mixed-Methods Study”

After the Focus Group

Your “data” will be either fieldnotes taken during the focus group or, more desirably, transcripts of the recorded exchange. If you do not have permission to record the focus group discussion, make sure you take very clear notes during the exchange and then spend a few hours afterward filling them in as much as possible, creating a rich memo to yourself about what you saw and heard and experienced, including any notes about body language and interactions. Ideally, however, you will have recorded the discussion. It is still a good idea to spend some time immediately after the conclusion of the discussion to write a memo to yourself with all the things that may not make it into the written record (e.g., body language and interactions). This is also a good time to journal about or create a memo with your initial researcher reactions to what you saw, noting anything of particular interest that you want to come back to later on (e.g., “It was interesting that no one thought Joe should quit his job, but in the other focus group, half of the group did. I wonder if this has something to do with the fact that all the participants were first-generation college students. I should pay attention to class background here.”).

Please thank each of your participants in a follow-up email or text. Let them know you appreciated their time and invite follow-up questions or comments.

One of the difficult things about focus group transcripts is keeping speakers distinct. Eventually, you are going to be using pseudonyms for any publication, but for now, you probably want to know who said what. You can assign speaker numbers (“Speaker 1,” “Speaker 2”) and connect those identifications with particular demographic information in a separate document. Remember to clearly separate actual identifications (as with consent forms) to prevent breaches of anonymity. If you cannot identify a speaker when transcribing, you can write, “Unidentified Speaker.” Once you have your transcript(s) and memos and fieldnotes, you can begin analyzing the data (chapters 18 and 19).

Advanced: Focus Groups on Sensitive Topics

Throughout this chapter, I have recommended against raising sensitive topics in focus group discussions. As an introvert myself, I find the idea of discussing personal topics in a group disturbing, and I tend to avoid conducting these kinds of focus groups. And yet I have actually participated in focus groups that do discuss personal information and consequently have been of great value to me as a participant (and researcher) because of this. There are even some researchers who believe this is the best use of focus groups ( de Oliveira 2011 ). For example, Jordan et al. ( 2007 ) argue that focus groups should be considered most useful for illuminating locally sanctioned ways of talking about sensitive issues. So although I do not recommend the beginning qualitative researcher dive into deep waters before they can swim, this section will provide some guidelines for conducting focus groups on sensitive topics. To my mind, these are a minimum set of guidelines to follow when dealing with sensitive topics.

First, be transparent about the place of sensitive topics in your focus group. If the whole point of your focus group is to discuss something sensitive, such as how women gain support after traumatic sexual assault events, make this abundantly clear in your consent form and recruiting materials. It is never appropriate to blindside participants with sensitive or threatening topics .

Second, create a confidentiality form (figure 12.2) for each participant to sign. These forms carry no legal weight, but they do create an expectation of confidentiality for group members.

In order to respect the privacy of all participants in [insert name of study here], all parties are asked to read and sign the statement below. If you have any reason not to sign, please discuss this with [insert your name], the researcher of this study, I, ________________________, agree to maintain the confidentiality of the information discussed by all participants and researchers during the focus group discussion.

Signature: _____________________________ Date: _____________________

Researcher’s Signature:___________________ Date:______________________

Figure 12.2 Confidentiality Agreement of Focus Group Participants

Third, provide abundant space for opting out of the discussion. Participants are, of course, always permitted to refrain from answering a question or to ask for the recording to be stopped. It is important that focus group members know they have these rights during the group discussion as well. And if you see a person who is looking uncomfortable or like they want to hide, you need to step in affirmatively and remind everyone of these rights.

Finally, if things go “off the rails,” permit yourself the ability to end the focus group. Debrief with each member as necessary.

Further Readings

Barbour, Rosaline. 2018. Doing Focus Groups . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Written by a medical sociologist based in the UK, this is a good how-to guide for conducting focus groups.

Gibson, Faith. 2007. “Conducting Focus Groups with Children and Young People: Strategies for Success.” Journal of Research in Nursing 12(5):473–483. As the title suggests, this article discusses both methodological and practical concerns when conducting focus groups with children and young people and offers some tips and strategies for doing so effectively.

Hopkins, Peter E. 2007. “Thinking Critically and Creatively about Focus Groups.” Area 39(4):528–535. Written from the perspective of critical/human geography, Hopkins draws on examples from his own work conducting focus groups with Muslim men. Useful for thinking about positionality.

Jordan, Joanne, Una Lynch, Marianne Moutray, Marie-Therese O’Hagan, Jean Orr, Sandra Peake, and John Power. 2007. “Using Focus Groups to Research Sensitive Issues: Insights from Group Interviews on Nursing in the Northern Ireland ‘Troubles.’” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 6(4), 1–19. A great example of using focus groups productively around emotional or sensitive topics. The authors suggest that focus groups should be considered most useful for illuminating locally sanctioned ways of talking about sensitive issues.

Merton, Robert K., Marjorie Fiske, and Patricia L. Kendall. 1956. The Focused Interview: A Manual of Problems and Procedures . New York: Free Press. This is one of the first classic texts on conducting interviews, including an entire chapter devoted to the “group interview” (chapter 6).

Morgan, David L. 1986. “Focus Groups.” Annual Review of Sociology 22:129–152. An excellent sociological review of the use of focus groups, comparing and contrasting to both surveys and interviews, with some suggestions for improving their use and developing greater rigor when utilizing them.

de Oliveira, Dorca Lucia. 2011. “The Use of Focus Groups to Investigate Sensitive Topics: An Example Taken from Research on Adolescent Girls’ Perceptions about Sexual Risks.” Cien Saude Colet 16(7):3093–3102. Another example of discussing sensitive topics in focus groups. Here, the author explores using focus groups with teenage girls to discuss AIDS, risk, and sexuality as a matter of public health interest.

Peek, Lori, and Alice Fothergill. 2009. “Using Focus Groups: Lessons from Studying Daycare Centers, 9/11, and Hurricane Katrina.” Qualitative Research 9(1):31–59. An examination of the efficacy and value of focus groups by comparing three separate projects: a study of teachers, parents, and children at two urban daycare centers; a study of the responses of second-generation Muslim Americans to the events of September 11; and a collaborative project on the experiences of children and youth following Hurricane Katrina. Throughout, the authors stress the strength of focus groups with marginalized, stigmatized, or vulnerable individuals.

Wilson, Valerie. 1997. “Focus Groups: A Useful Qualitative Method for Educational Research?” British Educational Research Journal 23(2):209–224. A basic description of how focus groups work using an example from a study intended to inform initiatives in health education and promotion in Scotland.

- Note that I have included a few examples of conducting focus groups with sensitive issues in the “ Further Readings ” section and have included an “ Advanced: Focus Groups on Sensitive Topics ” section on this area. ↵

A focus group interview is an interview with a small group of people on a specific topic. “The power of focus groups resides in their being focused” (Patton 2002:388). These are sometimes framed as “discussions” rather than interviews, with a discussion “moderator.” Alternatively, the focus group is “a form of data collection whereby the researcher convenes a small group of people having similar attributes, experiences, or ‘focus’ and leads the group in a nondirective manner. The objective is to surface the perspectives of the people in the group with as minimal influence by the researcher as possible” (Yin 2016:336). See also diversity focus group and convergence focus group.

A form of focus group construction in which people with diverse perspectives and experiences are chosen for inclusion. This helps the researcher identify commonalities across this diversity and/or note interactions across differences. Contrast with a convergence focus group

A form of focus group construction in which people with similar perspectives and experiences are included. These are particularly helpful for identifying shared patterns and group consensus. Contrast with a diversity focus group .

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 05 October 2018

Interviews and focus groups in qualitative research: an update for the digital age

- P. Gill 1 &

- J. Baillie 2

British Dental Journal volume 225 , pages 668–672 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

38k Accesses

72 Citations

22 Altmetric

Metrics details

Highlights that qualitative research is used increasingly in dentistry. Interviews and focus groups remain the most common qualitative methods of data collection.

Suggests the advent of digital technologies has transformed how qualitative research can now be undertaken.

Suggests interviews and focus groups can offer significant, meaningful insight into participants' experiences, beliefs and perspectives, which can help to inform developments in dental practice.

Qualitative research is used increasingly in dentistry, due to its potential to provide meaningful, in-depth insights into participants' experiences, perspectives, beliefs and behaviours. These insights can subsequently help to inform developments in dental practice and further related research. The most common methods of data collection used in qualitative research are interviews and focus groups. While these are primarily conducted face-to-face, the ongoing evolution of digital technologies, such as video chat and online forums, has further transformed these methods of data collection. This paper therefore discusses interviews and focus groups in detail, outlines how they can be used in practice, how digital technologies can further inform the data collection process, and what these methods can offer dentistry.

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Interviews in the social sciences

Professionalism in dentistry: deconstructing common terminology

A review of technical and quality assessment considerations of audio-visual and web-conferencing focus groups in qualitative health research, introduction.

Traditionally, research in dentistry has primarily been quantitative in nature. 1 However, in recent years, there has been a growing interest in qualitative research within the profession, due to its potential to further inform developments in practice, policy, education and training. Consequently, in 2008, the British Dental Journal (BDJ) published a four paper qualitative research series, 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 to help increase awareness and understanding of this particular methodological approach.

Since the papers were originally published, two scoping reviews have demonstrated the ongoing proliferation in the use of qualitative research within the field of oral healthcare. 1 , 6 To date, the original four paper series continue to be well cited and two of the main papers remain widely accessed among the BDJ readership. 2 , 3 The potential value of well-conducted qualitative research to evidence-based practice is now also widely recognised by service providers, policy makers, funding bodies and those who commission, support and use healthcare research.

Besides increasing standalone use, qualitative methods are now also routinely incorporated into larger mixed method study designs, such as clinical trials, as they can offer additional, meaningful insights into complex problems that simply could not be provided by quantitative methods alone. Qualitative methods can also be used to further facilitate in-depth understanding of important aspects of clinical trial processes, such as recruitment. For example, Ellis et al . investigated why edentulous older patients, dissatisfied with conventional dentures, decline implant treatment, despite its established efficacy, and frequently refuse to participate in related randomised clinical trials, even when financial constraints are removed. 7 Through the use of focus groups in Canada and the UK, the authors found that fears of pain and potential complications, along with perceived embarrassment, exacerbated by age, are common reasons why older patients typically refuse dental implants. 7

The last decade has also seen further developments in qualitative research, due to the ongoing evolution of digital technologies. These developments have transformed how researchers can access and share information, communicate and collaborate, recruit and engage participants, collect and analyse data and disseminate and translate research findings. 8 Where appropriate, such technologies are therefore capable of extending and enhancing how qualitative research is undertaken. 9 For example, it is now possible to collect qualitative data via instant messaging, email or online/video chat, using appropriate online platforms.

These innovative approaches to research are therefore cost-effective, convenient, reduce geographical constraints and are often useful for accessing 'hard to reach' participants (for example, those who are immobile or socially isolated). 8 , 9 However, digital technologies are still relatively new and constantly evolving and therefore present a variety of pragmatic and methodological challenges. Furthermore, given their very nature, their use in many qualitative studies and/or with certain participant groups may be inappropriate and should therefore always be carefully considered. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to provide a detailed explication regarding the use of digital technologies in qualitative research, insight is provided into how such technologies can be used to facilitate the data collection process in interviews and focus groups.

In light of such developments, it is perhaps therefore timely to update the main paper 3 of the original BDJ series. As with the previous publications, this paper has been purposely written in an accessible style, to enhance readability, particularly for those who are new to qualitative research. While the focus remains on the most common qualitative methods of data collection – interviews and focus groups – appropriate revisions have been made to provide a novel perspective, and should therefore be helpful to those who would like to know more about qualitative research. This paper specifically focuses on undertaking qualitative research with adult participants only.

Overview of qualitative research

Qualitative research is an approach that focuses on people and their experiences, behaviours and opinions. 10 , 11 The qualitative researcher seeks to answer questions of 'how' and 'why', providing detailed insight and understanding, 11 which quantitative methods cannot reach. 12 Within qualitative research, there are distinct methodologies influencing how the researcher approaches the research question, data collection and data analysis. 13 For example, phenomenological studies focus on the lived experience of individuals, explored through their description of the phenomenon. Ethnographic studies explore the culture of a group and typically involve the use of multiple methods to uncover the issues. 14

While methodology is the 'thinking tool', the methods are the 'doing tools'; 13 the ways in which data are collected and analysed. There are multiple qualitative data collection methods, including interviews, focus groups, observations, documentary analysis, participant diaries, photography and videography. Two of the most commonly used qualitative methods are interviews and focus groups, which are explored in this article. The data generated through these methods can be analysed in one of many ways, according to the methodological approach chosen. A common approach is thematic data analysis, involving the identification of themes and subthemes across the data set. Further information on approaches to qualitative data analysis has been discussed elsewhere. 1

Qualitative research is an evolving and adaptable approach, used by different disciplines for different purposes. Traditionally, qualitative data, specifically interviews, focus groups and observations, have been collected face-to-face with participants. In more recent years, digital technologies have contributed to the ongoing evolution of qualitative research. Digital technologies offer researchers different ways of recruiting participants and collecting data, and offer participants opportunities to be involved in research that is not necessarily face-to-face.

Research interviews are a fundamental qualitative research method 15 and are utilised across methodological approaches. Interviews enable the researcher to learn in depth about the perspectives, experiences, beliefs and motivations of the participant. 3 , 16 Examples include, exploring patients' perspectives of fear/anxiety triggers in dental treatment, 17 patients' experiences of oral health and diabetes, 18 and dental students' motivations for their choice of career. 19

Interviews may be structured, semi-structured or unstructured, 3 according to the purpose of the study, with less structured interviews facilitating a more in depth and flexible interviewing approach. 20 Structured interviews are similar to verbal questionnaires and are used if the researcher requires clarification on a topic; however they produce less in-depth data about a participant's experience. 3 Unstructured interviews may be used when little is known about a topic and involves the researcher asking an opening question; 3 the participant then leads the discussion. 20 Semi-structured interviews are commonly used in healthcare research, enabling the researcher to ask predetermined questions, 20 while ensuring the participant discusses issues they feel are important.

Interviews can be undertaken face-to-face or using digital methods when the researcher and participant are in different locations. Audio-recording the interview, with the consent of the participant, is essential for all interviews regardless of the medium as it enables accurate transcription; the process of turning the audio file into a word-for-word transcript. This transcript is the data, which the researcher then analyses according to the chosen approach.

Types of interview

Qualitative studies often utilise one-to-one, face-to-face interviews with research participants. This involves arranging a mutually convenient time and place to meet the participant, signing a consent form and audio-recording the interview. However, digital technologies have expanded the potential for interviews in research, enabling individuals to participate in qualitative research regardless of location.

Telephone interviews can be a useful alternative to face-to-face interviews and are commonly used in qualitative research. They enable participants from different geographical areas to participate and may be less onerous for participants than meeting a researcher in person. 15 A qualitative study explored patients' perspectives of dental implants and utilised telephone interviews due to the quality of the data that could be yielded. 21 The researcher needs to consider how they will audio record the interview, which can be facilitated by purchasing a recorder that connects directly to the telephone. One potential disadvantage of telephone interviews is the inability of the interviewer and researcher to see each other. This is resolved using software for audio and video calls online – such as Skype – to conduct interviews with participants in qualitative studies. Advantages of this approach include being able to see the participant if video calls are used, enabling observation of non-verbal communication, and the software can be free to use. However, participants are required to have a device and internet connection, as well as being computer literate, potentially limiting who can participate in the study. One qualitative study explored the role of dental hygienists in reducing oral health disparities in Canada. 22 The researcher conducted interviews using Skype, which enabled dental hygienists from across Canada to be interviewed within the research budget, accommodating the participants' schedules. 22

A less commonly used approach to qualitative interviews is the use of social virtual worlds. A qualitative study accessed a social virtual world – Second Life – to explore the health literacy skills of individuals who use social virtual worlds to access health information. 23 The researcher created an avatar and interview room, and undertook interviews with participants using voice and text methods. 23 This approach to recruitment and data collection enables individuals from diverse geographical locations to participate, while remaining anonymous if they wish. Furthermore, for interviews conducted using text methods, transcription of the interview is not required as the researcher can save the written conversation with the participant, with the participant's consent. However, the researcher and participant need to be familiar with how the social virtual world works to engage in an interview this way.

Conducting an interview

Ensuring informed consent before any interview is a fundamental aspect of the research process. Participants in research must be afforded autonomy and respect; consent should be informed and voluntary. 24 Individuals should have the opportunity to read an information sheet about the study, ask questions, understand how their data will be stored and used, and know that they are free to withdraw at any point without reprisal. The qualitative researcher should take written consent before undertaking the interview. In a face-to-face interview, this is straightforward: the researcher and participant both sign copies of the consent form, keeping one each. However, this approach is less straightforward when the researcher and participant do not meet in person. A recent protocol paper outlined an approach for taking consent for telephone interviews, which involved: audio recording the participant agreeing to each point on the consent form; the researcher signing the consent form and keeping a copy; and posting a copy to the participant. 25 This process could be replicated in other interview studies using digital methods.

There are advantages and disadvantages of using face-to-face and digital methods for research interviews. Ultimately, for both approaches, the quality of the interview is determined by the researcher. 16 Appropriate training and preparation are thus required. Healthcare professionals can use their interpersonal communication skills when undertaking a research interview, particularly questioning, listening and conversing. 3 However, the purpose of an interview is to gain information about the study topic, 26 rather than offering help and advice. 3 The researcher therefore needs to listen attentively to participants, enabling them to describe their experience without interruption. 3 The use of active listening skills also help to facilitate the interview. 14 Spradley outlined elements and strategies for research interviews, 27 which are a useful guide for qualitative researchers:

Greeting and explaining the project/interview

Asking descriptive (broad), structural (explore response to descriptive) and contrast (difference between) questions

Asymmetry between the researcher and participant talking

Expressing interest and cultural ignorance

Repeating, restating and incorporating the participant's words when asking questions

Creating hypothetical situations

Asking friendly questions

Knowing when to leave.

For semi-structured interviews, a topic guide (also called an interview schedule) is used to guide the content of the interview – an example of a topic guide is outlined in Box 1 . The topic guide, usually based on the research questions, existing literature and, for healthcare professionals, their clinical experience, is developed by the research team. The topic guide should include open ended questions that elicit in-depth information, and offer participants the opportunity to talk about issues important to them. This is vital in qualitative research where the researcher is interested in exploring the experiences and perspectives of participants. It can be useful for qualitative researchers to pilot the topic guide with the first participants, 10 to ensure the questions are relevant and understandable, and amending the questions if required.

Regardless of the medium of interview, the researcher must consider the setting of the interview. For face-to-face interviews, this could be in the participant's home, in an office or another mutually convenient location. A quiet location is preferable to promote confidentiality, enable the researcher and participant to concentrate on the conversation, and to facilitate accurate audio-recording of the interview. For interviews using digital methods the same principles apply: a quiet, private space where the researcher and participant feel comfortable and confident to participate in an interview.

Box 1: Example of a topic guide

Study focus: Parents' experiences of brushing their child's (aged 0–5) teeth

1. Can you tell me about your experience of cleaning your child's teeth?

How old was your child when you started cleaning their teeth?

Why did you start cleaning their teeth at that point?

How often do you brush their teeth?

What do you use to brush their teeth and why?

2. Could you explain how you find cleaning your child's teeth?

Do you find anything difficult?

What makes cleaning their teeth easier for you?

3. How has your experience of cleaning your child's teeth changed over time?

Has it become easier or harder?

Have you changed how often and how you clean their teeth? If so, why?

4. Could you describe how your child finds having their teeth cleaned?

What do they enjoy about having their teeth cleaned?

Is there anything they find upsetting about having their teeth cleaned?

5. Where do you look for information/advice about cleaning your child's teeth?

What did your health visitor tell you about cleaning your child's teeth? (If anything)

What has the dentist told you about caring for your child's teeth? (If visited)

Have any family members given you advice about how to clean your child's teeth? If so, what did they tell you? Did you follow their advice?

6. Is there anything else you would like to discuss about this?

Focus groups

A focus group is a moderated group discussion on a pre-defined topic, for research purposes. 28 , 29 While not aligned to a particular qualitative methodology (for example, grounded theory or phenomenology) as such, focus groups are used increasingly in healthcare research, as they are useful for exploring collective perspectives, attitudes, behaviours and experiences. Consequently, they can yield rich, in-depth data and illuminate agreement and inconsistencies 28 within and, where appropriate, between groups. Examples include public perceptions of dental implants and subsequent impact on help-seeking and decision making, 30 and general dental practitioners' views on patient safety in dentistry. 31

Focus groups can be used alone or in conjunction with other methods, such as interviews or observations, and can therefore help to confirm, extend or enrich understanding and provide alternative insights. 28 The social interaction between participants often results in lively discussion and can therefore facilitate the collection of rich, meaningful data. However, they are complex to organise and manage, due to the number of participants, and may also be inappropriate for exploring particularly sensitive issues that many participants may feel uncomfortable about discussing in a group environment.

Focus groups are primarily undertaken face-to-face but can now also be undertaken online, using appropriate technologies such as email, bulletin boards, online research communities, chat rooms, discussion forums, social media and video conferencing. 32 Using such technologies, data collection can also be synchronous (for example, online discussions in 'real time') or, unlike traditional face-to-face focus groups, asynchronous (for example, online/email discussions in 'non-real time'). While many of the fundamental principles of focus group research are the same, regardless of how they are conducted, a number of subtle nuances are associated with the online medium. 32 Some of which are discussed further in the following sections.

Focus group considerations

Some key considerations associated with face-to-face focus groups are: how many participants are required; should participants within each group know each other (or not) and how many focus groups are needed within a single study? These issues are much debated and there is no definitive answer. However, the number of focus groups required will largely depend on the topic area, the depth and breadth of data needed, the desired level of participation required 29 and the necessity (or not) for data saturation.

The optimum group size is around six to eight participants (excluding researchers) but can work effectively with between three and 14 participants. 3 If the group is too small, it may limit discussion, but if it is too large, it may become disorganised and difficult to manage. It is, however, prudent to over-recruit for a focus group by approximately two to three participants, to allow for potential non-attenders. For many researchers, particularly novice researchers, group size may also be informed by pragmatic considerations, such as the type of study, resources available and moderator experience. 28 Similar size and mix considerations exist for online focus groups. Typically, synchronous online focus groups will have around three to eight participants but, as the discussion does not happen simultaneously, asynchronous groups may have as many as 10–30 participants. 33

The topic area and potential group interaction should guide group composition considerations. Pre-existing groups, where participants know each other (for example, work colleagues) may be easier to recruit, have shared experiences and may enjoy a familiarity, which facilitates discussion and/or the ability to challenge each other courteously. 3 However, if there is a potential power imbalance within the group or if existing group norms and hierarchies may adversely affect the ability of participants to speak freely, then 'stranger groups' (that is, where participants do not already know each other) may be more appropriate. 34 , 35

Focus group management

Face-to-face focus groups should normally be conducted by two researchers; a moderator and an observer. 28 The moderator facilitates group discussion, while the observer typically monitors group dynamics, behaviours, non-verbal cues, seating arrangements and speaking order, which is essential for transcription and analysis. The same principles of informed consent, as discussed in the interview section, also apply to focus groups, regardless of medium. However, the consent process for online discussions will probably be managed somewhat differently. For example, while an appropriate participant information leaflet (and consent form) would still be required, the process is likely to be managed electronically (for example, via email) and would need to specifically address issues relating to technology (for example, anonymity and use, storage and access to online data). 32

The venue in which a face to face focus group is conducted should be of a suitable size, private, quiet, free from distractions and in a collectively convenient location. It should also be conducted at a time appropriate for participants, 28 as this is likely to promote attendance. As with interviews, the same ethical considerations apply (as discussed earlier). However, online focus groups may present additional ethical challenges associated with issues such as informed consent, appropriate access and secure data storage. Further guidance can be found elsewhere. 8 , 32

Before the focus group commences, the researchers should establish rapport with participants, as this will help to put them at ease and result in a more meaningful discussion. Consequently, researchers should introduce themselves, provide further clarity about the study and how the process will work in practice and outline the 'ground rules'. Ground rules are designed to assist, not hinder, group discussion and typically include: 3 , 28 , 29

Discussions within the group are confidential to the group

Only one person can speak at a time

All participants should have sufficient opportunity to contribute

There should be no unnecessary interruptions while someone is speaking

Everyone can be expected to be listened to and their views respected

Challenging contrary opinions is appropriate, but ridiculing is not.

Moderating a focus group requires considered management and good interpersonal skills to help guide the discussion and, where appropriate, keep it sufficiently focused. Avoid, therefore, participating, leading, expressing personal opinions or correcting participants' knowledge 3 , 28 as this may bias the process. A relaxed, interested demeanour will also help participants to feel comfortable and promote candid discourse. Moderators should also prevent the discussion being dominated by any one person, ensure differences of opinions are discussed fairly and, if required, encourage reticent participants to contribute. 3 Asking open questions, reflecting on significant issues, inviting further debate, probing responses accordingly, and seeking further clarification, as and where appropriate, will help to obtain sufficient depth and insight into the topic area.

Moderating online focus groups requires comparable skills, particularly if the discussion is synchronous, as the discussion may be dominated by those who can type proficiently. 36 It is therefore important that sufficient time and respect is accorded to those who may not be able to type as quickly. Asynchronous discussions are usually less problematic in this respect, as interactions are less instant. However, moderating an asynchronous discussion presents additional challenges, particularly if participants are geographically dispersed, as they may be online at different times. Consequently, the moderator will not always be present and the discussion may therefore need to occur over several days, which can be difficult to manage and facilitate and invariably requires considerable flexibility. 32 It is also worth recognising that establishing rapport with participants via online medium is often more challenging than via face-to-face and may therefore require additional time, skills, effort and consideration.

As with research interviews, focus groups should be guided by an appropriate interview schedule, as discussed earlier in the paper. For example, the schedule will usually be informed by the review of the literature and study aims, and will merely provide a topic guide to help inform subsequent discussions. To provide a verbatim account of the discussion, focus groups must be recorded, using an audio-recorder with a good quality multi-directional microphone. While videotaping is possible, some participants may find it obtrusive, 3 which may adversely affect group dynamics. The use (or not) of a video recorder, should therefore be carefully considered.