We have emailed you a PDF version of the article you requested.

Can't find the email?

Please check your spam or junk folder

You can also add [email protected] to your safe senders list to ensure you never miss a message from us.

Universe 25: The Mouse "Utopia" Experiment That Turned Into An Apocalypse

Complete the form below and we will email you a PDF version

Cancel and go back

IFLScience needs the contact information you provide to us to contact you about our products and services. You may unsubscribe from these communications at any time.

For information on how to unsubscribe, as well as our privacy practices and commitment to protecting your privacy, check out our Privacy Policy

Complete the form below to listen to the audio version of this article

Advertisement

Subscribe today for our Weekly Newsletter in your inbox!

James Felton

Senior Staff Writer

James is a published author with four pop-history and science books to his name. He specializes in history, strange science, and anything out of the ordinary.

Book View full profile

Book Read IFLScience Editorial Policy

DOWNLOAD PDF VERSION

The utopia in all its glory. Image credit: Yoichi R Okamoto, White House photographer (public domain, via Wikimedia Commons ).

Over the last few hundred years, the human population of Earth has seen an increase, taking us from an estimated one billion in 1804 to seven billion in 2017. Throughout this time, concerns have been raised that our numbers may outgrow our ability to produce food, leading to widespread famine.

Some – the Malthusians – even took the view that as resources ran out, the population would "control" itself through mass deaths until a sustainable population was reached. As it happens, advances in farming, changes in farming practices, and new farming technology have given us enough food to feed 10 billion people , and it's how the food is distributed which has caused mass famines and starvation. As we use our resources and the climate crisis worsens, this could all change – but for now, we have always been able to produce more food than we need, even if we have lacked the will or ability to distribute it to those that need it.

But while everyone was worried about a lack of resources, one behavioral researcher in the 1970s sought to answer a different question: what happens to society if all our appetites are catered for, and all our needs are met? The answer – according to his study – was an awful lot of cannibalism shortly followed by an apocalypse.

John B Calhoun set about creating a series of experiments that would essentially cater to every need of rodents, and then track the effect on the population over time. The most infamous of the experiments was named, quite dramatically, Universe 25 .

In this study, he took four breeding pairs of mice and placed them inside a "utopia". The environment was designed to eliminate problems that would lead to mortality in the wild. They could access limitless food via 16 food hoppers, accessed via tunnels, which would feed up to 25 mice at a time, as well as water bottles just above. Nesting material was provided. The weather was kept at 68°F (20°C), which for those of you who aren't mice is the perfect mouse temperature. The mice were chosen for their health, obtained from the National Institutes of Health breeding colony. Extreme precautions were taken to stop any disease from entering the universe.

As well as this, no predators were present in the utopia, which sort of stands to reason. It's not often something is described as a "utopia, but also there were lions there picking us all off one by one".

The experiment began, and as you'd expect, the mice used the time that would usually be wasted in foraging for food and shelter for having excessive amounts of sexual intercourse. About every 55 days, the population doubled as the mice filled the most desirable space within the pen, where access to the food tunnels was of ease.

When the population hit 620, that slowed to doubling around every 145 days, as the mouse society began to hit problems. The mice split off into groups, and those that could not find a role in these groups found themselves with nowhere to go.

"In the normal course of events in a natural ecological setting somewhat more young survive to maturity than are necessary to replace their dying or senescent established associates," Calhoun wrote in 1972 . "The excess that find no social niches emigrate."

Here, the "excess" could not emigrate, for there was nowhere else to go. The mice that found themself with no social role to fill – there are only so many head mouse roles, and the utopia was in no need of a Ratatouille -esque chef – became isolated.

"Males who failed withdrew physically and psychologically; they became very inactive and aggregated in large pools near the center of the floor of the universe. From this point on they no longer initiated interaction with their established associates, nor did their behavior elicit attack by territorial males," read the paper. "Even so, they became characterized by many wounds and much scar tissue as a result of attacks by other withdrawn males."

The withdrawn males would not respond during attacks, lying there immobile. Later on, they would attack others in the same pattern. The female counterparts of these isolated males withdrew as well. Some mice spent their days preening themselves, shunning mating, and never engaging in fighting. Due to this they had excellent fur coats, and were dubbed, somewhat disconcertingly, the "beautiful ones".

The breakdown of usual mouse behavior wasn't just limited to the outsiders. The "alpha male" mice became extremely aggressive, attacking others with no motivation or gain for themselves, and regularly raped both males and females . Violent encounters sometimes ended in mouse-on-mouse cannibalism.

Despite – or perhaps because – their every need was being catered for, mothers would abandon their young or merely just forget about them entirely, leaving them to fend for themselves. The mother mice also became aggressive towards trespassers to their nests, with males that would normally fill this role banished to other parts of the utopia. This aggression spilled over, and the mothers would regularly kill their young. Infant mortality in some territories of the utopia reached 90 percent.

This was all during the first phase of the downfall of the "utopia". In the phase Calhoun termed the "second death", whatever young mice survived the attacks from their mothers and others would grow up around these unusual mouse behaviors. As a result, they never learned usual mice behaviors and many showed little or no interest in mating, preferring to eat and preen themselves, alone.

The population peaked at 2,200 – short of the actual 3,000-mouse capacity of the "universe" – and from there came the decline. Many of the mice weren't interested in breeding and retired to the upper decks of the enclosure, while the others formed into violent gangs below, which would regularly attack and cannibalize other groups as well as their own. The low birth rate and high infant mortality combined with the violence, and soon the entire colony was extinct . During the mousepocalypse, food remained ample, and their every need completely met.

Calhoun termed what he saw as the cause of the collapse "behavioral sink".

"For an animal so simple as a mouse, the most complex behaviors involve the interrelated set of courtship, maternal care, territorial defence and hierarchical intragroup and intergroup social organization," he concluded in his study.

"When behaviors related to these functions fail to mature, there is no development of social organization and no reproduction. As in the case of my study reported above, all members of the population will age and eventually die. The species will die out."

He believed that the mouse experiment may also apply to humans, and warned of a day where – god forbid – all our needs are met.

"For an animal so complex as man, there is no logical reason why a comparable sequence of events should not also lead to species extinction. If opportunities for role fulfilment fall far short of the demand by those capable of filling roles, and having expectancies to do so, only violence and disruption of social organization can follow."

At the time, the experiment and conclusion became quite popular, resonating with people's feelings about overcrowding in urban areas leading to "moral decay" (though of course, this ignores so many factors such as poverty and prejudice).

However, in recent times, people have questioned whether the experiment could really be applied so simply to humans – and whether it really showed what we believed it did in the first place.

The end of the mouse utopia could have arisen "not from density, but from excessive social interaction," medical historian Edmund Ramsden said in 2008 . “Not all of Calhoun’s rats had gone berserk. Those who managed to control space led relatively normal lives.”

As well as this, the experiment design has been criticized for creating not an overpopulation problem, but rather a scenario where the more aggressive mice were able to control the territory and isolate everyone else. Much like with food production in the real world, it's possible that the problem wasn't of adequate resources, but how those resources are controlled.

THIS WEEK IN IFLSCIENCE

Article posted in.

overpopulation,

weird and wonderful

More Nature Stories

link to article

North America's Denali Fault Was Ripped Apart By Two Clashing Landmasses

There Are Actually Four Distinct Species Of Giraffe – And Their Skulls Confirm It

The USA Is Set To Finally Get An Official National Bird

IFLScience We Have Questions: What Attacks You In The Most Remote Place On Earth?

A New North Pole, Bubble-Butt Turtles, And Testing Ancient Hangover Cures

IFLScience The Big Questions: Why Do Humans Love Playing Competitive Games?

This Old Experiment With Mice Led to Bleak Predictions for Humanity’s Future

From the 1950s to the 1970s, researcher John Calhoun gave rodents unlimited food and studied their behavior in overcrowded conditions

Maris Fessenden ; Updated by Rudy Molinek

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7c/36/7c36a5fc-01a8-4877-aeb4-ad87704efcf2/calhounj.jpg)

What does utopia look like for mice and rats? According to a researcher who did most of his work in the 1950s through 1970s, it might include limitless food, multiple levels and secluded little condos. These were all part of John Calhoun’s experiments to study the effects of population density on behavior. But what looked like rodent paradises at first quickly spiraled into out-of-control overcrowding, eventual population collapse and seemingly sinister behavior patterns.

In other words, the mice were not nice.

Working with rats between 1958 and 1962, and with mice from 1968 to 1972, Calhoun set up experimental rodent enclosures at the National Institute of Mental Health’s Laboratory of Psychology. He hoped to learn more about how humans might behave in a crowded future. His first 24 attempts ended early due to constraints on laboratory space. But his 25th attempt at a utopian habitat, which began in 1968, would become a landmark psychological study. According to Gizmodo ’s Esther Inglis-Arkell, Calhoun’s “Universe 25” started when the researcher dropped four female and four male mice into the enclosure.

By the 560th day, the population peaked with over 2,200 individuals scurrying around, waiting for food and sometimes erupting into open brawls. These mice spent most of their time in the presence of hundreds of other mice. When they became adults, those mice that managed to produce offspring were so stressed out that parenting became an afterthought.

“Few females carried pregnancies to term, and the ones that did seemed to simply forget about their babies,” wrote Inglis-Arkell in 2015. “They’d move half their litter away from danger and forget the rest. Sometimes they’d drop and abandon a baby while they were carrying it.”

A select group of mice, which Calhoun called “the beautiful ones,” secluded themselves in protected places with a guard posted at the entry. They didn’t seek out mates or fight with other mice, wrote Will Wiles in Cabinet magazine in 2011, “they just ate, slept and groomed, wrapped in narcissistic introspection.”

Eventually, several factors combined to doom the experiment. The beautiful ones’ chaste behavior lowered the birth rate. Meanwhile, out in the overcrowded common areas, the few remaining parents’ neglect increased infant mortality. These factors sent the mice society over a demographic cliff. Just over a month after population peaked, around day 600, according to Distillations magazine ’s Sam Kean, no baby mice were surviving more than a few days. The society plummeted toward extinction as the remaining adult mice were just “hiding like hermits or grooming all day” before dying out, writes Kean.

Calhoun launched his experiments with the intent of translating his findings to human behavior. Ideas of a dangerously overcrowded human population were popularized by Thomas Malthus at the end of the 18th century with his book An Essay on the Principle of Population . Malthus theorized that populations would expand far faster than food production, leading to poverty and societal decline. Then, in 1968, the same year Calhoun set his ill-fated utopia in motion, Stanford University entomologist Paul Ehrlich published The Population Bomb . The book sparked widespread fears of an overcrowded and dystopic imminent future, beginning with the line, “The battle to feed all of humanity is over.”

Ehrlich suggested that the impending collapse mirrored the conditions Calhoun would find in his experiments. The cause, wrote Charles C. Mann for Smithsonian magazine in 2018, would be “too many people, packed into too-tight spaces, taking too much from the earth. Unless humanity cut down its numbers—soon—all of us would face ‘mass starvation’ on ‘a dying planet.’”

Calhoun’s experiments were interpreted at the time as evidence of what could happen in an overpopulated world. The unusual behaviors he observed—such as open violence, a lack of interest in sex and poor pup-rearing—he dubbed “behavioral sinks.”

After Calhoun wrote about his findings in a 1962 issue of Scientific American , that term caught on in popular culture, according to a paper published in the Journal of Social History . The work tapped into the era’s feeling of dread that crowded urban areas heralded the risk of moral decay.

Events like the murder of Kitty Genovese in 1964—in which false reports claimed 37 witnesses stood by and did nothing as Genovese was stabbed repeatedly—only served to intensify the worry. Despite the misinformation, media discussed the case widely as emblematic of rampant urban moral decay. A host of science fiction works—films like Soylent Green , comics like 2000 AD —played on Calhoun’s ideas and those of his contemporaries . For example, Soylent Green ’s vision of a dystopic future was set in a world maligned by pollution, poverty and overpopulation.

Now, interpretations of Calhoun’s work have changed. Inglis-Arkell explains that the main problem of the habitats he created wasn’t really a lack of space. Rather, it seems likely that Universe 25’s design enabled aggressive mice to stake out prime territory and guard the pens for a limited number of mice, leading to overcrowding in the rest of the world.

However we interpret Calhoun’s experiments, though, we can take comfort in the fact that humans are not rodents. Follow-up experiments by other researchers, which looked at human subjects, found that crowded conditions didn’t necessarily lead to negative outcomes like stress, aggression or discomfort.

“Rats may suffer from crowding,” medical historian Edmund Ramsden told the NIH Record ’s Carla Garnett in 2008, “human beings can cope.”

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

Maris Fessenden | | READ MORE

Maris Fessenden is a freelance science writer and artist who appreciates small things and wide open spaces.

Rudy Molinek | READ MORE

Rudy Molinek is Smithsonian magazine's 2024 AAAS Mass Media Fellow.

Share this post

Universe 25: The Heaven for Mice that turned into Hell

In this edition, we delve into the captivating stories of two groundbreaking psychology experiments: Universe 25 , the mouse utopia, and the Asch Conformity Experiment , offering profound insights into human and animal behaviour in society.

The Universe 25 Experiment: A Mouse Utopia Turns Awry

In the 1960s, a scientist named John B. Calhoun designed a grand experiment with 4 pairs of mice, one that would unravel the mysteries of society and overcrowding. It was called "Universe 25," a place where mice could live in a paradise untouched by predators, with endless food and water, and a climate-controlled environment. A utopia for mice , it seemed.

As the mouse population continued to swell, a strange transformation occurred. Despite the availability of enough resources, the mice began to exhibit various abnormal, often destructive behaviours. This included hyperaggression, failure to breed normally, infant abandonment, and, in certain cases, cannibalism. Some male mice formed gangs that attacked each other, while others withdrew completely , refusing to interact with others or breed, which Calhoun referred to as "the beautiful ones." Instead of participating in the violence and chaos, they withdrew. They no longer reproduced, grooming themselves endlessly and seeking solitude. The beautiful ones had distanced themselves from the social frenzy.

The population began to decline as violence, aggression, and withdrawal took their toll. The mouse society was collapsing, and no amount of resources or space could reverse the damage. Calhoun observed that, even when provided with all the necessities, the mice were unable to recover.

The peak population was reached around day 560 with around 2200 mice, thereafter population declined and by around day 920, the mice had died out completely.

Universe 25 was not just a mouse experiment; it offered profound insights into the behaviour of living beings, including humans, in crowded environments. It revealed the far-reaching effects of overpopulation on societal dynamics and individual mental health.

The similarities between Universe 25 and human society are striking. As cities grow more crowded, we see similar patterns emerge: heightened competition for resources, increased stress, and even individuals withdrawing from society . Calhoun's experiment serves as a stark reminder of what can occur when we disregard the consequences of overcrowding.

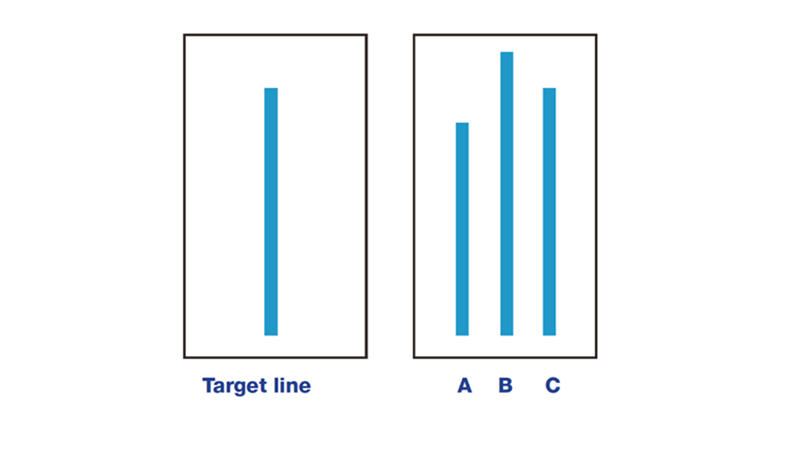

The Asch Conformity Experiment , conducted by Solomon Asch in 1951, aimed to understand how people behave in groups and whether they are willing to conform to group opinion, even if it goes against what they know to be true.

In the experiment, participants were brought into a room with other people, who were actually actors working with the experimenter. The group was shown a simple line on one card and then three lines on another card, one of which was the same length as the line on the first card. Each person had to say out loud which line matched the first one.

The catch was that the actors were told to give the wrong answer on purpose. As a result, the real participant was often the last to speak. They had to decide whether to stick with what they knew was right or go along with the group's incorrect answer.

The findings were surprising. Many participants chose to conform and give the wrong answer because they didn't want to stand out or appear different from the group. They were influenced by the group's opinion.

This experiment demonstrated the power of social pressure and the human tendency to conform to the group, even when the group is clearly wrong. It also highlighted the importance of independence and critical thinking in the face of peer pressure.

The Asch Conformity Experiment has had a lasting impact on our understanding of social psychology and how people respond to group dynamics and the fear of being the odd one out.

Learned something new today? Go ahead, share this post!

Discussion about this post

Excellent information and educational as well! Gives an interesting insight into human/social behaviour.

Wow. The mice experiment blew me. Just under 3 years to extinct even with all the life necessities

Ready for more?

Universe 25 Experiment: How Did the Mouse Utopia Project Turned Into Population Demise?

During the 1960s, a project called Universe 25 experiment was conducted to study the social behavior of rodents. Known as the most terrifying experiment in science, the research provided insights into the future of humanity.

What is Universe 25 Experiment?

The Universe 25 is a series of experiments conducted in the 1960s and 1970s by American ethologist John B. Calhoun. Its goal is to understand the effects of overpopulation on the social behavior of mice and use it in exploring the consequences of overpopulation and resource depletion in human society.

In this study, Calhoun designed a utopian environment that can house up to 5,000 mice. It is made of a 9-square-foot enclosure divided into four interconnected pens. In each pen, food hoppers, water dispensers, and nesting boxes were provided on each level. Four pairs of healthy, young mice were introduced in the enclosure, and their population was expected to grow exponentially given the abundant resources and the absence of predators.

The development of the study was divided into four phases. In the Strive phase, the mice population adapted to their new environment and started reproducing. As the population doubled every 55 days, social hierarchies among the rodents began to form. In the Exploit phase, the population doubled every 32 days, and the mice could also fully exploit the available resources. However, during this time, the first signs of social stress began to develop.

The Equilibrium phase began when the mice population reached its peak. This period is characterized by a slowing down growth rate and population stabilization. Behavioral changes such as social distress also started to appear at this phase. In the Decline phase, the rodent population decreased, with the social structure breaking down entirely. Despite the availability of resources, the population crashed, and the mice failed to regain social cohesion.

As the Universe 25 experiment progressed, Calhoun observed several alarming behavioral changes among the mice. First, overcrowding led the mice to become more aggressive and have hostile interactions with each other. Increased competition for space and social standing led to more violent behavior. Some mice labeled "The Beautiful Ones" preferred to withdraw from society and focus their attention on eating without showing interest in reproduction. Uncontrolled infanticide and rampant killing, these factors all led to the decline in the mice population.

READ ALSO : Israeli Mice Experiment Suggests Human Life Could Extend Up to 23 Percent

Implications for Human Society

Although there are differences between mice and human behavior, the result of the Universe 25 experiment provided grim predictions for the future of humanity . Population growth can trigger competition for resources which, when not properly managed, can lead to violence, social unrest, and breakdown in social structures. Overcrowding can also cause social isolation and mental health problems such as stress, depression, and loneliness.

Experts agree that the result of this experiment serves as a reminder about the importance of resource management, sustainable development, and the need to address social problems brought about by overpopulation. It shows that despite the abundance of food and water, personal space is also essential to prevent societal collapse.

RELATED ARTICLE : Observing Natural Behavior of Mice With Machine Learning as a New Approach in Neurological Experiments on Animals

Check out more news and information on Mice Experiments in Science Times.

Most Popular

'Obelisks' Found Inside Half of the World's Human Population Could Act as 'Stealthy Evolutionary Passengers'

Astronomers Reveal Mysterious Plasma Channels in the Milky Way

Avian Influenza Surge Prompts Emergency Declaration in California

Persistent Coughs Are Everywhere: Here's What Experts Think Is Causing It

NASA's Parker Solar Probe Redefines Limits With Closest Approach to Sun

Latest stories.

Are California Squirrels Carnivorous? Bizarre Behavior Observed by Scientists in Local Rodents

Charged Particles From Sun Hit Earth: Here's What Scientists Expect to Happen Next

Why the Barn Owl's Gleaming White Underbelly Is a Strategic Advantage for Hunting

Giant Predatory Amphipod Discovered Thriving 8,000 Meters Below in Extreme Deep-Sea Environment

Subscribe to the science times.

Sign up for our free newsletter for the Latest coverage!

Recommended Stories

Voyager 2’s Historic Uranus Flyby May Have Captured Rare Event, Changing Scientists’ View of the Planet

Is the Ozone Layer Repairing Itself? Scientists Think So

SpaceX Dragon Successfully Docks With ISS, Delivering 6,000 Pounds of Supplies

Colorectal Cancer Deaths Increasing Among Millennials and Gen X: Learn the Warning Signs

- May 2022, Issue 1

- Research Ethics

Universe 25 Experiment

A series of rodent experiments showed that even with abundant food and water, personal space is essential to prevent societal collapse, but universe 25's relevance to humans remains disputed..

Stephanie "Annie" Melchor is a freelancer and former intern for The Scientist .

View full profile.

Learn about our editorial policies.

J une 22, 1972. John Calhoun stood over the abandoned husk of what had once been a thriving metropolis of thousands. Now, the population had dwindled to just 122, and soon, even these inhabitants would be dead.

Calhoun wasn’t the survivor of a natural disaster or nuclear meltdown; rather, he was a researcher at the National Institute of Mental Health conducting an experiment into the effects of overcrowding on mouse behavior. The results , laid bare at his feet, had taken years to play out.

Universe 25 Experiment Explained

In 1968, Calhoun had started the experiment by introducing four mouse couples into a specially designed pen—a veritable rodent Garden of Eden—with numerous “apartments,” abundant nesting supplies, and unlimited food and water. The only scarce resource in this microcosm was physical space, and Calhoun suspected that it was only a matter of time before this caused trouble in paradise.

Calhoun had been running similar experiments with rodents for decades but had always had to end them prematurely, ironically because of laboratory space constraints, says Edmund Ramsden, a science historian at Queen Mary University of London. This iteration, dubbed Universe 25, was the first crowding experiment he ran to completion.

As he had anticipated, the utopia became hellish nearly a year in when the population density began to peak, and then population growth abruptly and dramatically slowed. Animals became increasingly violent, developed abnormal sexual behaviors, and began neglecting or even attacking their own pups.

Eventually Universe 25 took another disturbing turn. Mice born into the chaos couldn’t form normal social bonds or engage in complex social behaviors such as courtship, mating, and pup-rearing. Instead of interacting with their peers, males compulsively groomed themselves; females stopped getting pregnant. Effectively, says Ramsden, they became “trapped in an infantile state of early development,” even when removed from Universe 25 and introduced to “normal” mice. Ultimately, the colony died out. “There’s no recovery, and that’s what was so shocking to [Calhoun],” says Ramsden.

Debunking Popular Interpretations of Universe 25

Calhoun wasn’t shy about anthropomorphizing his findings, binning rodents into categories such as “juvenile delinquents” and “social dropouts,” and others seized on these human parallels. Population growth in the 1970s was swelling, and films such as Soylent Green tapped into growing fears of overpopulation and urban violence. In a 2011 article , Ramsden writes that Calhoun’s studies were brandished by others to justify population control efforts largely targeted at poor and marginalized communities.

But Ramsden notes that Calhoun didn’t necessarily think humanity was doomed. In some of Calhoun’s other crowding experiments, rodents developed innovative tunneling behaviors, while in others, adding more rooms allowed the animals to live in the high-density environment without being forced into unwanted contact with others, largely minimizing the negative social consequences. According to Ramsden, Calhoun wanted these findings to influence the architectural design of prisons, mental hospitals, and other buildings prone to crowding. Writing in a report summary in 1979, Calhoun noted that “no single area of intellectual effort can exert a greater influence on human welfare than that contributing to better design of the built environment.”

Relevance and Criticisms of the Universe 25 Experiment

Looking back on the Universe 25 experiment with present day scientific perspective, the limits of its interpretations are evident. The research was largely observational and subjective. Calhoun described his study as “not normal science,” referring to it instead as an “observation and reconstruction of a process.” 2 Observational studies have a higher risk of bias and confusing correlation with causation. 3 Scientists have suggested that Universe 25 suffers from inaccurate interpretation of experimental outcomes, methods, and potentially confounding variables, 4 which reflect information bias . 3 For instance, at the time that Calhoun presented and published Universe 25’s results, his peers inquired about unsanitary animal husbandry and a lack of quantitative stress hormone measurements as potential confounding or missing information pertinent to Calhoun’s conclusions. 2

Importantly, despite popular interpretations of Universe 25 deeming it informative about urban crowding, many human studies on crowding and population density have yielded inconsistent results. 4 Behavioral scientists today largely acknowledge that how humans experience and respond to crowding is governed by a range of individual-specific social and psychological factors , including personal autonomy and social roles or contexts. 4 In some ways, this aligns with how Calhoun discussed his Universe 25 findings, not as effects of population density per se but effects of altered social interactions . 2 Additionally, the Universe 25 experiment did not address systemic determinants of well-being at the time, nor does it reflect present-day systems that are endemic to the human experience. The societal implications of increased population density and its effects on human beings are a far throw from Universe 25’s experimental design and the behavioral changes that Calhoun observed in his caged rodent experiments. 2,4

Finally, from an ethical standpoint, Calhoun’s experiments would not be permitted today. The mouse universes that Calhoun created intentionally placed its study subjects into constructed environments that caused harm. The study conditions were maintained despite evident animal distress, and many preventable casualties ensued. 2 This goes against current regulatory safety standards for animal research. 5

Which scientist conducted the Universe 25 experiment?

- John B. Calhoun led the Universe 25 experiment , which examined the long-term effects of increasing population density and resulting social stressors on mice living in a constructed environment. 2

How many times was the Universe 25 experiment repeated?

- Universe 25 was one long-term experiment in a series of mouse studies. The entire research series involved Calhoun’s constructed Mortality-Inhibiting Environment for Mice , and each universe examined separate mouse populations and conditions. Calhoun stated that the Universe 25 experiment involved the largest mouse population and longest follow up period. 2

What is a behavioral sink?

- In overcrowding rat studies that Calhoun performed before the Universe 25 experiment, he observed that individual rats began to associate feeding with the company of other rats, which led to the learned behavior of voluntary crowding despite insufficient resources at a crowded site and available resources elsewhere. He termed this specific voluntary crowding a behavioral sink . 1 Calhoun also observed this learned behavior in mice during the Universe 25 experiment. 2

Were the results of the Universe 25 experiment reproduced by other scientists?

- The social effects of population density vary between organisms and populations. Calhoun’s work inspired many scientists to focus on behavioral studies , but the specific experiment has not been replicated. 4,6

What is the criticism of Universe 25?

- The Universe 25 experiment faces several scientific limitations, including experimental biases inherent to observational studies, misinterpretation and unsubstantiated extrapolation to human experiences, and ethical concerns related to animal care . 2-5

This article was originally published on May 2, 2022. It was updated on May 28, 2024 by Deanna MacNeil , PhD .

- Calhoun JB. Population density and social pathology . Scientific American Magazine . 1962;206(2):139.

- Calhoun JB. Death squared: the explosive growth and demise of a mouse population . Proc R Soc Med . 1973;66(1P2):80-88.

- Boyko EJ. Observational research opportunities and limitations . J Diabetes Complications . 2013;27(6):642-648.

- Ramsden E. The urban animal: population density and social pathology in rodent and humans . Bull World Health Organ . 2009;87(2):82.

- Animal Research Advisory Committee (ARAC) Guidelines . OACU. Accessed May 28, 2024.

- Ramsden E, Adams J. Escaping the laboratory: The rodent experiments of John B. Calhoun and their cultural influence . J Soc Hist . 2009;42(3):761-797.

Membership Open House!

Interested in exclusive access to more premium content?

Home > ETDS > Dissertations and Theses > 1429

Dissertations and Theses

Behavioral changes due to overpopulation in mice.

James Robert Hammock , Portland State University

Portland State University. Department of Psychology

First Advisor

Ronald E. Smith

Term of Graduation

Summer 1971

Date of Publication

Document type, degree name.

Master of Science (M.S.) in Psychology

Crowding stress, Mice -- Behavior

10.15760/etd.1428

Physical Description

1 online resource (46 pages)

Previous research has found that if a population were allowed to exceed a comfortable density level, then many catastrophic events occurred such as increased mortality among the young, cannibalism, homosexuality, and lack of maternal functions. The most influential researcher in this area is Calhoun (1962), after whose experimental design a pilot study was fashioned to replicate his results. The results of this pilot study inspired a more detailed research project of which this thesis is an account.

Forty-eight albino mice of the Swiss Webster strain were divided into three groups of sixteen each. Each group consisted of ten females and six males chosen randomly; two groups were to serve as experimental groups and the other group as the control. The experimental groups were placed in an apparatus 15 5/8” x 20 1/2"x 8" and the control group in an apparatus 47 7/8" x 61 1/2" x 8". The three groups were allowed to multiply freely with nesting material, food and water provided proportionately as their numbers grew. The experimental groups were allowed to overpopuate while the control group was not.

There were six behavior variables noted as the experiment proceeded: (1) grooming, (2) homosexuality, (3) nest building, (4) retrieving of young, (5) fighting, and (6) mortality of the young. It was predicted that grooming, nest building, and retrieving of the young would decrease in frequency as the population increased, while fighting, homosexuality and mortality of the young would increase with the rising population density. The experiment was conducted for six months and fourteen days.

The result of this experiment was a total lack of overpopulation. The two experimental groups never weaned any pups though they produced many, and the control group grew to the comfortable limits of its apparatus and then ceased weaning any further pups. In an effort to ascertain the reasons for these results, one of the experimental groups was artificially reduced in number; whereupon it promptly weaned forty-one percent of its first litter, thirty percent of its second, and none of its third. At the time of its first weaning, this group was technically overpopulated.

In conclusion a hypothesis is proposed to explain the results. It is felt that each population has an innate knowledge of its comfortable limits with regard to density and will maintain this crucial density level if necessary. The group's ability to control its population is directly related to a time factor in that if a population were allowed to approach its crucial density level gradually it would not exceed it; however if there were little or no approach time, then this level would be exceeded.

In Copyright. URI: http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ This Item is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this Item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s).

If you are the rightful copyright holder of this dissertation or thesis and wish to have it removed from the Open Access Collection, please submit a request to [email protected] and include clear identification of the work, preferably with URL.

Persistent Identifier

http://archives.pdx.edu/ds/psu/10046

Recommended Citation

Hammock, James Robert, "Behavioral Changes Due to Overpopulation in Mice" (1971). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 1429. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.1428

Since October 09, 2013

Included in

Applied Behavior Analysis Commons , Experimental Analysis of Behavior Commons , Other Animal Sciences Commons

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Featured Collections

- All Authors

- Schools & Colleges

- Dissertations & Theses

- PDXOpen Textbooks

- Conferences

- Collections

- Disciplines

- Faculty Expert Gallery

- Submit Research

- Faculty Profiles

- Terms of Use

- Feedback Form

Home | About | My Account | Accessibility Statement | Portland State University

Privacy Copyright

Tea in the ancient world

Tuesday, september 1, 2020, calhoun's universe 25 mice experiments; overpopulation effects related to modern social themes.

This is the third post in a row branching off the subject of tea, which I will get back to. It has been nice mixing things up.

I've just ran across a really interesting summary of some social structure oriented experiments on mice by a researcher in the late 60s through the 70s, John Calhoun's rat and mice experiments related to the effects of overpopulation.

There's a lot to get through, and I have a number of comments on how I see it potentially relating to what we experience today, so I'll need to keep this moving. I'll pass on a short summary of what I see as the overview, then cite a summary I ran across that offers a somewhat abbreviated and highly interpreted version, then comments on what doesn't seem right in that. Then on to comments about how I see the mice and rat findings relating to current social trends, which play out in the most obvious fashion in social media use patterns and social groups.

That topic outline:

1. overview of the experiments (focusing mainly on one set of findings)

2. summary article

3. likely errors in that summary

4. key findings overview

5. links to modern trends, especially related to social media trends and groups

6. final conclusions

1. Overview of the experiments

The "Universe 25" part relates to one experiment trial, obviously enough the 25th in a series. The idea was to set up rat or mice "utopias," isolated living conditions where they had ample food, shelter, safety, and separated living areas to see what the forms or stages of their breeding and behavior would be, as their population naturally increased. If I'm remembering correctly Calhoun anticipated a relatively high population would develop relatively quickly, about as fast as normal breeding timing allowed for, and the results didn't match that.

I'll add links to two separate research papers by him, and one multiple-part video interview. I would recommend that anyone who finds this theme as interesting as I do doesn't take my summary and conclusions as accurate, reviewing his take as well. Some of what I've seen in summaries seems clearly wrong, and I'll speculate beyond what the original researcher concluded. It may be hard to clearly identify that cut-off, even though I'll try to make it explicit.

It's hard to separate why he started doing this, what the original goals were, from later positioning and research direction, on to what he had already discovered and was looking to clarify. In a sense what he initially expected doesn't matter, versus what he later found out through results. Even his own interpretation is worth keeping separate from the actual findings details, noting what seems to be clearly identified facts (breeding population numbers, behavior patterns) from cause and effect sequences, why the rats and mice were doing what they were doing. Earlier on he had been working with rats and changed that to mice, so by the time of "Universe 25" he was dealing with mice populations instead.

I won't go into the details of the experiment set-up, how the zones were constructed, what the animals were fed, how initial subjects were selected, and so on; all of that is in the summary papers. It's probably as well to let that medium length summary cover the findings from this basic framing, and then correct errors (as I interpret them), and condense that down to a clear set of simple findings, to work with in extension to compare to human social trends.

That last step of a comparison with people seems to have dropped out in review of this work back in the 70s and 80s, but that probably relates mostly to me only reading and citing some earlier content. It would be easy to conclude that people and mice are two different things, and that these isolated and unusual circumstances just never would relate directly to actual human living conditions or behavior patterns.

It's also worth noting that in a field I did actually study more, philosophy, entire directions and approaches were deemed unfruitful at different times, so that if you go back 45 years to read what philosophy was and how it was approached all of that would be unfamiliar. It's a little strange seeing some of the same thing occur related to core texts that never really went away, like Plato or Kant's work, so that earlier interpretations just seem odd in comparison to the terms they later came to be defined in, and the conclusions.

In a second video section of the one reference Calhoun anticipated that there was a window of time to apply these findings to develop human social sciences, and that the same patterns wouldn't occur in human societies until around the present time (2020; now), and not in the more extreme forms until around the time-frame of 2040. He thought the damage would have been done by then, that overpopulation would have led to the negative changes seen in rats before that time, on the order of when there were 7-8 billion people alive, so now. Why he thinks there is an earlier window for resolving root causes prior to the full impact of social crowding or overpopulation effects setting in becomes clear in the findings details; keep that connection in mind.

That raises an interesting tangent; in that second video segment he is able to accurately predict human population change over the next 50 years, up until now, because he did that simple graphing in 1970 in that video reference. It looked a lot like what I've just shown here, a log-log scale graph of time and population, with his mapped pattern shown as a straight line.

He also predicted that population control measures would have been implemented by the beginning of this century, or there would be a natural tendency for populations to stabilize, although he didn't anticipate that process would be relatively complete until there were around 9 billion people, in the 2040's time-frame. So far all that seems right. It might seem like all that is a completely different subject than what these rats went though, and that I never do get it to link together. That's it, I won't; Calhoun's expectations of predicting future human society changes is really kind of a separate subject, an extension of what I'll consider.

The main core finding relates to the concept of " behavioral sink :"

"Behavioral sink" is a term invented by ethologist John B. Calhoun to describe a collapse in behavior which can result from overcrowding.

2. Universe 25 summary article (Quora answer)

If this is a personal summary then this link is already a complete attribution, but more typically these are cut and pasted, and the real source is missing, which is even implied in the question framing. Either way:

What is something that you read recently and is worth sharing

Read about The "Universe 25" experiment it is one of the most terrifying experiments in the history of science, which, through the behavior of a colony of mice, is an attempt by scientists to explain human societies.

The idea of "Universe 25" Came from the American scientist John Calhoun, who created an "ideal world" in which hundreds of mice would live and reproduce. More specifically, Calhoun built the so-called "Paradise of Mice", a specially designed space where rodents had Abundance of food and water, as well as a large living space.

In the beginning, he placed four pairs of mice that in a short time began to reproduce, resulting in their population growing rapidly. However, after 315 days their reproduction began to decrease significantly. When the number of rodents reached 600, a hierarchy was formed between them and then the so-called "wretches" appeared. The larger rodents began to attack the group, with the result that many males begin to "collapse" psychologically. As a result, the females did not protect themselves and in turn became aggressive towards their young. As time went on, the females showed more and more aggressive behavior, isolation elements and lack of reproductive mood. There was a low birth rate and, at the same time, an increase in mortality in younger rodents.

Then, a new class of male rodents appeared, the so-called "beautiful mice". They refused to mate with the females or to "fight" for their space. All they cared about was food and sleep. At one point, "beautiful males" and "isolated females" made up the majority of the population. As time went on, juvenile mortality reached 100% and reproduction reached zero.

Among the endangered mice, homosexuality was observed and, at the same time, cannibalism increased, despite the fact that there was plenty of food. Two years after the start of the experiment, the last baby of the colony was born. By 1973, he had killed the last mouse in the Universe 25. John Calhoun repeated the same experiment 25 more times, and each time the result was the same.

Calhoun's scientific work has been used as a model for interpreting social collapse, and his research serves as a focal point for the study of urban sociology.

3. Likely errors in that summary

It's not bad, actually. I'm interpreting these as errors, based on reading two of Calhoun's own papers, and other summaries and interpretations, and watching a video of two interviews of Calhoun, and one other interview summary (and I'll add the links at the end).

Errors / clarification:

1. 25 trials: He didn't run 25 identical experiments, he kept changing the parameters, and kept finding similar trends. Maybe he did run "universes" 25 through 50 using identical parameters but it seems more likely this is just an error. He even changed the initial form from using rats to using mice. It makes for an interesting context for it to have worked out exactly the same 25 tests in a row (here described as "running" 25 times after one complete test), but it still works if the findings kept repeating, but in different forms based on using different set-ups and contexts, which is how I understood it really did happen.

2. Ideal world / paradise: it was a test for checking on how overpopulation worked out in a rodent test environment, so in a sense that was a "mouse paradise," but in another sense it was set up to run until failure. Calhoun would've been surprised if the mice had developed some sort of ideal mouse-society structures and behaviors. There was ample food, water, living space, restriction of external threats, and elimination of disease, to the extent possible, but of course it was going to get hellish eventually.

3. Steady state prior to decline, rodents attacking each other: a number of distinct social roles came up, not just that of larger male dominant mice who attacked others. I'll map out my understanding of the results in the next section but this requires that breakdown to serve as corrective commentary:

alpha male: one role was that of dominant males, who would take over residence areas and only allow females to enter. It could be clearer-seeming different in different citations--but males who had dropped intention of breeding may have been allowed in the same areas. At any rate the main point of this simple summary is right, except that it doesn't frame this point as clearly as it might, that some males set up local zones they dominated individually. Calhoun wasn't using the "alpha male" terminology; that seems to have evolved in common use later, or else he just didn't take it up.

females related to alpha male: this didn't seem like some odd version of human polygamy, pair-bonding extending to a group, as in a Mormon society, but per one description something like this seems to have occurred. Then most of the mice also lived grouped as crowded into common spaces, including both less dominant males and females.

males other than alpha males: the dominance competition didn't end with some few males claiming territory; it continued in the form of ongoing fighting between other males. The "winner" in these competitions wouldn't be completely consistent, although some male mice would more consistently lose or else drop out of this competition. A concept of a "beta male" doesn't emerge, but two other forms of non-competitive males are described. In the video interview Calhoun describes the stress levels of mice being tested and indicates that stress levels were very high for mice living in the crowded group areas. I think this is a critical point, that the reactions of the mice all relate mostly to long term stress responses.

probers: some male mice transitioned to performing relatively constant exploratory behavior, even though there really wasn't much for them to keep exploring. This seemed to be described as a fall-back behavior related to continually losing the dominance competition.

It could be completely unrelated but Jordan Peterson once described how in early experiments done on cats (which would now be regarded as unacceptably inhumane) parts of their brain could be removed, even most of them, and the cats could still function normally, for the most part, but would become hyper-exploratory. It was as if the normal function of many higher order types of "reasoning" in cats led to restricting or tuning behavior in cats, in different ways, and without that processing the cats just kept looking around, as these mice did. Attitudes towards animal testing seems to have changed a lot; none of these types of things would seem as acceptable now.

beautiful ones: per my read on Calhoun's comments these included both males and females, not just males, as summarized in that Quora answer. These mice are identified as socially non-competitive, not interacting with others in the same ways, only concerned with eating, sleeping, and grooming. For whatever reason they hadn't been raised with normal social conditioning and normal behaviors, or else they chose to reject those. Calhoun's description, from his 1962 paper:

Two other types of male emerged, both of which had resigned entirely from the struggle for dominance. They were, however, at exactly opposite poles as far as their levels of activity were concerned. The first were completely passive and moved through the community like somnambulists. They ignored all the other rats of both sexes, and all the other rats ignored them. Even when the females were in estrus, these passive animals made no advances to them. And only very rarely did other males attack them or approach them for any kind of play. To the casual observer the passive animals would have appeared to be the healthiest and most attractive members of the community. They were fat and sleek, and their fur showed none of the breaks and bare spots left by the fighting in which males usually engage. But their social disorientation was nearly complete.

Calhoun seems to link the degraded behavior patterns with females putting less emphasis on raising offspring, paying less attention to them. In some cases female mice would even kill their offspring, or neglect them to the extent that the young mice died. These social patterns, of social non-participation or other pathological tendencies, seemed to relate to these female parenting patterns affecting the next generations, brought on by changes in female mouse behavior. It's not completely clear that this was mostly related to stress response. The isolated females should have experienced less stress, intuitively, but since the mouse social patterns led to eventual extinction this couldn't have resulted in a stable set of responses.

Other factors brought up but not treated at length include infant mortality, a lack of breeding (failing to have any offspring), homosexuality (or something like that, related behaviors), and cannibalism. I'll cover more about those in a next section summarizing results more clearly, again in the form of my own interpretation.

4. Key findings overview

What all this means relates to two separate levels of analysis: the points I didn't describe yet (eg. why the mice committed cannibalism), and how to interpret these patterns.

Calhoun takes one very large step beyond drawing experiment conclusions in the second video interview, extending what he identified as discovered application to human interactions, then projecting that onto a time-frame for when these types of experiences would apply more directly to people. He never "pushes" that far enough to speculate those specific forms, how human societies or individual behaviors would fail in the same ways, at least in that video. For example, he doesn't guess if cannibalism will occur among people in greater numbers, or homosexuality, or predict how the dominant male to group of related females breeding pattern would be enacted, since humans could never experience directly parallel circumstances.

Let's start with the granular description first, how those other details seem to fit in with the rest, then move on more to interpretation after that.

cannibalism / homosexual behavior: these Calhoun seems to interpret as related as behavioral anomalies, not so different than the continual exploration / "probing" behavior. It seems to be how the mice react to high-stress conditions that shatter their normal social role patterns. Aggressive behavior also relates; the descriptions of mice continually fighting ties to these others. A comment in a Quora discussion claimed that Calhoun was really trying to link homosexuality with crowding and psychological stress, but in at least the two papers and two short video interviews he really doesn't expand on that topic at all. No doubt other commentary and interpretation by others has added more to that discussion, and it's possible Calhoun addresses it further in other material.

Of course the mice aren't pursuing homosexual, pair-bonded relationships, they are only mimicking the sex act with other male mice. In common understanding this could relate to dominance demonstration (although obviously I'm not trained in psychology, so I'm not trying to pass on a developed interpretation). Per the short references it didn't seem to be tied to that, just to abnormal behavior instead, as the fighting not related to sexual selection dominance was, or the mice and rats biting each others' tails without clear purpose. From the context of Calhoun's comments it didn't even seem like the mice were necessarily seeking sexual gratification, as if they could just be behaving somewhat erratically for parting ways with pre-conditioned social responses so drastically.

Calhoun's own related description from the 1962 paper is interesting:

Below the dominant males both on the status scale and in their level of activity were the homosexuals-a group perhaps better described as pan sexual. These animals apparently could not discriminate between appropriate and inappropriate sex partners. They made sexual advances to males, juveniles and females that were not in estrus. The males, including the dominants as well as the others of the pansexuals' own group, usually accepted their attentions. The general level of activity of these animals was only moderate. They were frequently attacked by their dominant associates, but they very rarely contended for status.

Cannibalism wasn't explained or expanded on either. It seems implied that both young mice and adults were killed and eaten, related to stress response, but without a more complete analysis or without more background that pattern isn't clear.

die-off: this seems to relate to mice losing social conditioning to fulfill normal roles, with that new set of mice lacking that conditioning simply stopping breeding. Calhoun defines the transition in terms of a "first death" when successful, normal social conditioning stopped, in terms of that step leading to death, and also the more metaphorical death of the mouse culture (or end of successful social conditioning patterns, if one would rather). It's odd that this could occur so completely that the mouse colonies would completely cease to exist, but that's an interesting and disturbing part of the study findings, that they are counter-intuitive.

This is why Calhoun interprets these findings as being so dire, in relation to drawing a parallel with human societies. He doesn't just see these patterns as indicating unhealthy trends that may repeat among people, but as representing the potential downfall of human societies as a whole. It would take time, and would occur over some stages, as it did with the mice. Even if it would never relate to this final level (extinction) the earlier negative patterns aren't as reversible as they might seem, at least in the case of the mice.

Intuitively the alpha males and related females should have been able to set up a new mouse behavior paradigm that could repeat over the long term, but that's not what they observed. This interim steady-state context was only stable over the short term, with some degree of further decline built into those conditions, at least within the context of that experiment.

lessons learned: really I didn't get far with this part, even though it's really the likely crux. Calhoun mentioned that in other experiments it was possible to set up a similar context, along with learned-response reward systems, to build in goals and evolving positive response cycles for the mice, and avoid the negative conditions and final terminal end state. Those lessons and conditions may really fall too far from human experience to be as useful, or that really could relate to the entire experiment structure.

If humans could be confined to a limited space, with limited outlets, for example in an underground city space, some of this context and the findings may apply more directly. Even then people are more self-aware than mice or rats, with the potential to set up more shared boundaries, roles, and restrictions, and may be able to avoid some of the same endpoint states, even under the most identical conditions imaginable. It would be interesting to compare these results to studies of social behavior patterns among long term prison inmate populations, to see if there really would be any carry-over. It seems a stretch, as if the parallel would be more complete observed over human lifetimes, versus decades, with prison population turn-over renewing social expectations and perspectives too much to replicate these negative transitions.

interpretation and criticism of Calhoun's work : Edmund Ramsden & Jon Adams wrote a good 2008 summary of the experiments, specific findings, conclusion interpretations, and later acceptance and rejection of these ideas and methodology in Escaping the Laboratory: The Rodent Experiments of John B. Calhoun & Their Cultural Influence .

The point here is to consider these ideas, and then interpret other later isolated but related patterns in human societies as potentially similar or not. It's a different kind of thing to speculate about how patterns found in rodent social experiments might inform us of human society behavior. It might seem like I've just contradicted myself, but as I see it the two themes can stay separate. We can look for and consider underlying human society patterns that superficially mirror these study results, without ever expecting the studies to necessarily predict or relate to the other human conditions. Partial parallels could be interesting and informative, even without expecting underlying causal connections.

It would be interesting if the forms of societal decay Calhoun expected happen next, or if that's what we are actually witnessing now. As I've interpreted the little I've ran across he saw his own work as a starting point, not a detailed model, and definitely not predictive in that sense. That's in spite of him anticipating that population growth would become a problem on a sociological level, as it was experienced individually through impact to social forms, not just in terms of resource depletion or scarcity.

In a Smithstonian Magazine reference a slight variation in interpretation is mentioned:

Now, interpretations of Calhoun’s work has changed. Inglis-Arkell explains that the habitats he created weren’t really overcrowded, but that isolation enabled aggressive mice to stake out territory and isolate the beautiful ones. She writes, "Instead of a population problem, one could argue that Universe 25 had a fair distribution problem."

At least at that level of detail this doesn't seem to add much. The mice had more space than they needed, and unlimited food, so the limitation was on social relationships, between individuals competing for dominance. It's odd framing access to female breeding partners as a "distribution problem," although I guess in some sense that might work.

I think it helps to keep the timeline in mind. I've cited Calhoun's published work in two forms from 1962 and 1973, with a video reference from 1970 (all in a references section following). The IBM PC was introduced in 1981, and the world wide web (file-type conventions) formally created around 1991, so Calhoun wasn't able to factor in the source of the main changes we've experienced in the last 40 years. The following section doesn't do that either, but it does raise some related social changes that at least superficially resemble his mice behavior patterns.

5. Links to modern trends, including social media groups and trends

This would also have to seem a stretch, and the ideas in this section will be quite speculative, but hear me out. The idea here is to consider to what extent patterns in modern societies or social groupings may already replicate some of these isolated-mouse-society patterns, and why. Obviously I'm not suggesting that human societies are falling apart in the same ways that these experiments predicted. The idea is to consider some related effects, without the causes necessarily being similar.

incels (involuntary celibates) : obviously just summarizing this pattern or social group as either of those, a pattern or a social group, will be too problematic to fully justify, but there is an obvious clear parallel here. I'll use a Wikipedia summary to cover that background faster:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Incel

Incels (/ˈɪnsɛlz/ IN-selz), a portmanteau of "involuntary celibates", are members of an online subculture who define themselves as unable to find a romantic or sexual partner despite desiring one. Discussions in incel forums are often characterized by resentment, misogyny, misanthropy, self-pity and self-loathing, racism, a sense of entitlement to sex, and the endorsement of violence against sexually active people.

The American nonprofit Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) described the subculture as "part of the online male supremacist ecosystem" that is included in their list of hate groups. Incels are mostly male and heterosexual, and many sources report that incels are predominantly white. Estimates of the overall size of the subculture vary greatly, ranging from thousands to hundreds of thousands.

At least six mass murders, resulting in a total of 44 deaths, have been committed since 2014 by men who have either self-identified as incels or who had mentioned incel-related names and writings in their private writings or Internet postings. Incel communities have been criticized by the media and researchers for being misogynistic, encouraging violence, spreading extremist views, and radicalizing their members...

So really two aspects seem to carry over: the theme of some males (mostly males) representing themselves as not being able to successfully pair bond or mate with females, and resulting violence. With "only" six mass murders being referenced one might wonder if that's a higher than average case proportion in the US (it surely is; the point here is that mass murder should be more of an anomaly than it actually is).

It's not clear what causes this, why that pattern shows up as something a group of people all experience, but a sub-theme relates to an odd description of the context and potential causes:

The "black pill" generally refers to a set of commonly-held beliefs in incel communities, which include biological determinism, fatalism, and defeatism for unattractive people... as "a profoundly sexist ideology that ... amounts to a fundamental rejection of women's sexual emancipation, labeling women shallow, cruel creatures who will choose only the most attractive men if given the choice."

...a belief that the entire social system was broken and that one's place in the system was not something any individual could change. An incel who has "taken the black pill" has adopted the belief that they are hopeless, and that their lack of success romantically and sexually is permanent regardless of any changes they might try to make to their physical appearance, personality, or other characteristics.

A bit extreme, right? One part stands out to me, describing women as "choos[ing] only the most attractive men if given the choice." There's no way to successfully do it, but that needs to be unpacked, to determine why that's not just a natural outcome, and why it relates to a problem of this importance in this context. The higher level description is interesting, that "the entire social system was broken."

On to the guessing part, but first one more observation that links to that. A online contact (/ friend; that boundary is hard to pin down) mentioned trying out dating apps (programs) and not being successful, not doing much dating as a result. Someone else commented in that Facebook discussion--this was all being hashed out in an open forum--that per their experience the most attractive few men and women tend to choose each other and meet through dating apps, and the majority who aren't as attractive also choose those potential partners and then aren't selected. That implies a lot more for sweeping general patterns than I intend, but how that could and probably does work, to some degree, is obvious enough.

Next one would wonder about the expected normal, conventional pattern of people of all different levels of being "naturally attractive"--possessing symmetrical features, clear skin, athletic appearance, lack of noticeable negative features, etc.--pairing based on shared interests, and acceptance that their partner doesn't need to look like a model or movie star. Intuitively that should happen, and to some extent it must.

One factor or driver that might well "throw a spanner into the works" could be social status and income level related to males. Men would tend to over-emphasize appearance, per my experience as a male, and general perception, but women would factor in a broader set of concerns, including appearance and these other two concerns. It's not unheard of for people to describe themselves as "sapio-sexual," valuing intelligence, and other shared interests could always factor in (reading preference, passtimes, social groupings, personal interests, liking tea).

But if we can assume that physical attractiveness and social status, largely linked to income, might be over-riding factors for females judging males then that could leave a significant majority of males out. Many might see only the second half as open to being changed, their status, and even that might not be easy. Of course weight issues and such can be addressed, or personal style concerns. Sloppy clothing styles, poor grooming, poor posture, or even wearing a fedora might limit males' visual appeal.

Let's consider one or two alpha-male cases that might help place this, if only to a limited degree. In the realm of Instagram influencers Dan Bilzerian is famous for putting out an image of himself as being surrounded by beautiful women who accompany him (an ex-military guy known for physique, attractiveness, cultivating image through gun ownership, and playing poker). That's probably about as close as we could get to the alpha-male Universe 25 direct mapping. Of course some of that is just image; he probably earns significant income from leveraging that social media persona, so to some degree that's also a business branding issue. Then there are Hollywood stars who date many young women, a pattern that would repeat in more conventional forms. Those women date multiple successful men too, no doubt, so the parallel isn't as clearly formed.

In both these extreme and relatively unconventional examples the paradigm of attractive men and multiple women partnering gets extended. We're not seeing how people across a broader spectrum are in any way blocked from dating or finding a long term mate by this. Only the mouse-society case of a significant number of dominant males maintaining multiple partners--both the very successful "alphas" and the temporarily successful mixed population mice--seems to set up this set of circumstances.

There are two ways this same selection paradigm could result in the involuntarily single-male outcome (here still on the human case):

1. females are also involuntarily single, or at least voluntarily so. This seems most likely, since the other outcome seems a stretch, extensive polygamy occurring.

2. some males are either dating multiple women or serial dating to a degree that throws off the equitable pairing conclusion. Maybe this happens, but given that all this is a tangent to a tangent I should really let this drop at this point. I'll move on to considering another related societal pattern.

incel caricatures:

I won't spend too much time on this but it is interesting, how evolved these images and stereotypes become in online discussions.

What Does 'Chad' Mean? The Odd Way Incel Men On Reddit And 4Chan Use It To Describe Certain Guys

According to Incel Wiki, "A chad is someone who can elicit near universal positive female sexual attention at will. A chad tends to be between an '8' to a '10' on the decile scale, has an extremely high income and/or an extreme amount of social status. A sexually active chad has sex with a wide variety of women, and has exclusive access to Stacy...

The stereotype evolves, only partly as a joke, with the standard description for an "incel" tied to the typical understanding:

The people in these "incel" circles are portraying the "alphas" negatively on purpose, and also really do identify with the cartoon-like incel character, but the joking around shifts the intentions and forms.

childlessness by choice: the obvious example for this pattern also relating to people seems to relate to Japanese society as a whole. Rather than summarize that from personal knowledge I'll cite the first related article turned up by Google search:

Japan's Births Decline To Lowest Number On Record (NPR, December 2019)

The country's health ministry announced Tuesday that the number of babies born in 2019 fell by an estimated 5.9% this year, to 864,000. It's the first time since 1899, when the government began tracking the data, that the number has dipped below 900,000, according to The Asahi Shimbun....

What accounts for the steep drop in births? The health ministry points to the declining numbers of people of reproductive age, as the offspring of baby boomers get older.

That joins other factors — namely the immense burden shouldered by Japanese women to do housework and child care by themselves, and a culture that makes it difficult to both have a job outside the home and be a mother. Younger generations of Japanese women have increasingly opted to continue working, rather than get married, have children and give up their careers...

...Marriage rates in Japan have halved since the early 1970s, and birth rates have declined in tandem.

It's probably as well if I don't try to link this to broader patterns in other places, or back to the mice. In both cases mice and people are intentionally not reproducing, and it's enough to note that this is an isolated case related to degree, but not in relation to it only happening there. From the framing here it doesn't have anything to with stress response, directly, but instead relates to opposing demands.

This is really more interesting related to Calhoun's predictions for societal changes during this century than for being a clear tie-in with his experimental results. He anticipated this, a leveling off of population increase, just not necessarily in this form. It definitely could be unrelated and coincidental that outcomes from separate causal patterns matched up.

the "beautiful ones" mice case:

The financial well-being of Millennials is complicated. The individual earnings for young workers have remained mostly flat over the past 50 years. But this belies a notably large gap in earnings between Millennials who have a college education and those who don’t.

...On the whole, Millennials are starting families later than their counterparts in prior generations. Just under half (46%) of Millennials ages 25 to 37 are married, a steep drop from the 83% of Silents who were married in 1968. The share of 25- to 37-year-olds who were married steadily dropped for each succeeding generation, from 67% of early Boomers to 57% of Gen Xers...

In 2016, 48% of Millennial women (ages 20 to 35 at the time) were moms. When Generation X women were the same age in 2000, 57% were already mothers, similar to the share of Boomer women (58%) in 1984.

Of course that mentioned the trend of Millennial generation members to not develop independent living arrangements as often or as quickly as in past generations, tied to higher housing costs and higher student loan debt burdens.

Obviously I'm not implying that Millennial generation members are more likely to drop out social role attributes. Due to a mix of complex factors it is more difficult for those at the lower end of the economic earnings spectrum to take up those life choices or conditions as quickly, or for as many to.

Again it's not directly related to any of these specific changes, but Calhoun expected changes to broad social patterns, which he related to population growth, to be initiated in the mid 1980s (in 1970) and then become more completely transitioned by 2040. It's interesting keeping that time-frame expectation in mind while considering these types of actually-experienced changes.

Calhoun was a bit idealistic, thinking that people could shed the light of day on underlying social change factors and make conscious choices to affect both individual experience and societal level transitions by the mid 1980s. 50 years later it's still not clear if vaguely related patterns are playing out, or what is causing the changes we definitely do see happening.

Back to the mice

A picture emerges here of these mice predicting some trends we see now. That's either because that model accurately predicted societal changes 50 years ago, or it's because I've just cherry-picked modern culture themes that at least superficially link to those in the study. It's more the latter, for sure, but all of these themes are interesting to consider on their own, and also as potentially connected patterns.

Society isn't fragmenting and breaking down though. Or is it? To the extent that it may be crowding and mate selection issues don't seem to be at the center of the problems.

Other forms of societal pressures may match some of these patterns, as economic issues result in unusual levels of personal stress. Atypical levels of social contact alone seem unlikely to cause the same types of behavioral patterns seen in the mice.